‘The Spawnmeister’ and the MV Shellfish Group have championed Island aquaculture for nearly 50 years.

People on Martha’s Vineyard are excited about shellfish, and with good reason. In 2018, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s marine science journal released a survey study illustrating how bivalves like oysters, quahogs, and soft-shelled clams can filter excess nitrogen in waterways. Long before this scientific epiphany, shellfish were considered an essential economic (and gastronomic) resource on the Island, especially in the early and mid-eighties, when wild fin fisheries were being decimated due to overfishing, habitat degradation, and pollution.

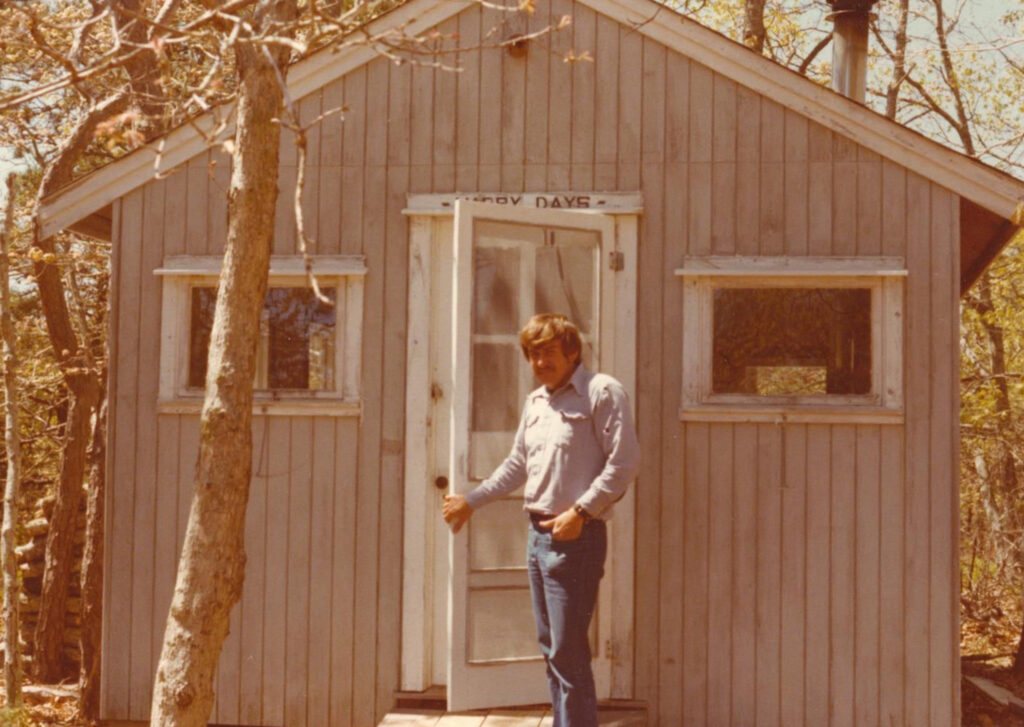

The wild shellfish industry was booming back in 1976, when Rick Karney washed ashore to take a job with the late Michael Wild, who at the time was serving as Coastal Planner for the Martha’s Vineyard Commission. Wild, a longtime conservationist, sought to bring together all the local shellfish constables, along with representatives from each Island town, to hire a dedicated shellfish biologist who would help establish a regional aquaculture program, and construct and oversee a public hatchery. Karney, who currently holds the title of Founder and Director Emeritus of the Martha’s Vineyard Shellfish Group, recalls that “that first year, a couple shellfish constables got together on basically a nonexistent budget and built a little lean-to greenhouse and started experimenting. Solar energy was just starting to be all the rage; there was a local group that wanted to work with us, and that’s how the solar hatchery was born.”

In 2016, after more than 40 years as Director of the Shellfish Group, Karney stepped down, and Emma Green-Beach, the special projects manager at the Hatchery, assumed the position. Although he’s no longer at the helm of the nonprofit, Karney continues to play an active role in promoting shellfish aquaculture on the Vineyard. He believes the organization has a bright future and that the new team has already accomplished a great deal. “A lot of programs the group is doing now are giving people an understanding of the importance of shellfish, and fostering a love for that aspect of Island culture,” Karney said. “Back then, people knew how to shuck. They knew how to rake — there is a need to build that culture up again and keep it going.”

Bluedot Living: Did you always want to become a biologist?

Rick Karney: I have been a biologist since I was a little kid. They used to call me “Butterfly Boy,” because I would have a butterfly net and I would go around the neighborhood and catch butterflies. Where I grew up, in New Jersey, my folks had a little boat. We would go to one of the freshwater lakes about an hour away from my house, or sometimes we would go to the Jersey shore, which was a two-hour drive. I was always just fascinated by being on the water — all the life, the birds, the fish, the insects. My father had a net that two people pulled to catch bait. I remember pulling in the net and there would be little blowfish, sometimes crabs, all sorts of cool stuff. So you could say I always had an interest in biology and the natural world.

I have been a biologist since I was a little kid. They used to call me butterfly boy because I would have a butterfly net and I would go around the neighborhood and catch butterflies.

– Rick Karney

I went to Rutgers and was in a biology pre-med program, although I wasn’t even really thinking I wanted to go into medicine. I got out of there and was primed to go to graduate school, but I wanted to take some time off because I didn’t know what I wanted to study. I ended up getting a job as a technician at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. I was at this little field station on the eastern shore of Virginia. That’s when I really got involved in aquaculture and shellfish culture, and from there I sort of made up my mind: “that’s what I want to do.”

BDL: How did you first find the Island?

RK: I came to the Island in 1976. I had never even been here before. I applied for a job with the Wampanoag Tribe as a shellfish biologist and didn’t get it. At the time, Mike Wild was leading the Martha’s Vineyard Commission’s coastal planning efforts; he called me and said there was a job at the Commission that I might be a good fit for that was pretty similar to the position with the Tribe.

Remember, when I started getting going, all this work was pretty new. We were trying different approaches to starting a hatchery. While all this was going on, the wild fisheries were still very prolific, but [they] started to decline pretty soon after I showed up on the scene. The price of seafood eventually increased to a point where aquaculture started to really take off.

Back then, you could go into any bar, restaurant, or coffee shop, and within fifteen or twenty minutes, someone would be talking shellfish. That’s how central it was.

– Rick Karney, MV Shellfish Group Director Emeritus

Mike started organizing all these parts together — a representative from each select board, all the shellfish constables — into one big group. Just around that time, there was a big oil spill in Buzzards Bay. There was a settlement, and part of the settlement involved funding to try and reseed the area that was affected, and replenish the shellfish that were lost. So the constables would get this seed from the Aquaculture Research Corporation in Dennis (back then it was known as the Cultured Clam), and were trying out different nursery methods.

BDL: What was shellfishing like back then?

RK: In those days we had a summer that ended on Labor Day, and Islanders made their living on scalloping, and they got family permits and would dig for quahogs; people lived off the water. Once people heard that shellfish aquaculture was possible on the Vineyard, and things like scallop and oyster seed could be grown locally, that was like the golden goose for that part of the community.

Back then, you could go into any bar, restaurant, or coffee shop, and within fifteen or twenty minutes, someone would be talking shellfish. That’s how central it was. It used to be taught, it was a strong tradition that was passed down generationally.

BDL: How was the Shellfish Group established? What spurred the idea to build the solar hatchery?

RK: The spring after I arrived, the MVC ended up getting a little grant for me. Shortly thereafter, the plans came together for the solar hatchery, and there was a group called the Energy Resource Group that was into alternative energy. We worked with that group and designed the hatchery from the bottom up.

There was a program that provided funding for coastal communities to mitigate any problems that might be associated with offshore oil development. Mike knew about this program, and because nobody else had their act together, we had no competition for the funding. There was a lot of weird politics involved with getting the funding, but we eventually made it through, and we finished construction in around 1981. We were the first public solar-powered shellfish hatchery — it was a brand-new idea.

BDL: Was the community enthusiastic to support this kind of organization when you first began? Has the level of enthusiasm among shellfishermen changed over the years?

RK: The Vineyard has always had this shellfish culture. That’s how people paid their bills. That’s how people ate. There is a huge historical aspect to shellfish on the Island, but a lot of that knowledge and energy is being lost. The Shellfish Group recently hired an outreach coordinator, Nina E. Ferry Montanile. They’ve been doing a program on how to shuck oysters, and they are starting up their shellfish 4-H program again. Basically, the goal is to get people to understand the importance of shellfish, and foster a love for that aspect of the culture.

There was a time here when everyone knew how to use a rake to dig quahogs, they knew how to shuck. There is a need to build that up and keep it alive here. People go to DisneyLand to see Mickey Mouse, and people used to come to the Vineyard because they could grab a rake or just a bucket and go get dinner.

People go to DisneyLand to see Mickey Mouse, and people used to come to the Vineyard because they could grab a rake or just a bucket and go get dinner.

– Rick Karney

Jack Blake was one of the trainees in my early training group. He has been one of the main proponents of aquaculture and just shellfishing in general. He is the reason many of these younger folks are out there now — he inspired this whole generation of aquaculturists.

BDL: There is a lot of promising research, especially recently, about how good shellfish are for the environment. Does this inspire you? Have you altered your approach to your work?

RK: When I first got involved in aquaculture, you were growing shellfish to be purely a food resource. I don’t know exactly when, but at some point there was a realization that a lot of the pollution issues were related to nitrogen. The more populated areas became, the more we had issues with water quality. People started to look at how shellfish can consume the algae that are growing at densities too high because of that nitrogen overload.

Especially oysters — they are a keystone species, so they provide habitat for all these other species. Shellfish create all these little nooks and crannies where marine life can move in and begin to populate that area. This all supports the larger fish population. It’s amazing to see how shellfish can address so many different issues we experience, and more research is coming out all the time.

There were a lot of environmental issues occuring in the 80s, and although we didn’t really have a name for it back then, climate change was definitely messing things up for the marine ecosystem here. The wild shellfish industry started to fail because of a confluence of these things. We used to have really cold winters here, and then year by year we got less ice on all the ponds. Those cold temperatures and ice used to keep green crabs, which are a major predator of shellfish, somewhat at bay. Then we started getting these mild winters, and the crabs started overwhelming the fishery.

When we started hearing about how shellfish can filter out nitrogen and eliminate some of the eutrophication [excessive richness of nutrients in water, often due to runoff, which leads to algae blooms], I was really inspired. It was like this “aha” moment. Then studies started coming out about all the nutritional benefits of shellfish — omega 3s and everything. They become this perfect food, on top of cleaning the water and everything else. The Island started to see shellfish as much more than just a food resource.

BDL: Do you shellfish at all, commercially or recreationally?

RK: I used to shellfish recreationally a lot in Virginia. When I got here, I was doing the work at the hatchery and out on the water all week, so it felt like I didn’t have the time. I used to go out with the shellfish constables and would get my fill of quahogs and oysters and steamers. Now I have bad knees and a bad shoulder, so my rake has been relegated to the closet, more or less. To me, it’s just as satisfying to support the local aquaculturists by buying food from them.

BDL: Do you have a favorite shellfish to eat? What’s your favorite dish involving shellfish?

RK: My favorite shellfish used to be scallops, but it’s hard to say — they’re all amazing. In recent years I have really come to appreciate oysters. Oysters are a little more versatile. You can eat them on the half shell, you can eat them baked, fried, pretty much any way you can think of. And the gastronomical history of oysters is incredible. You look at old oyster cookbooks, and it’s amazing how creative people have been with preparing oysters over the years. I really like oyster stew, but oysters on the half-shell are pretty hard to beat.

I used to bring this sort of oyster casserole to these slow food potlucks that the Ag Society hosted. It’s based on a recipe called oysters primavera that I got from a friend. It’s oysters and broccoli and cheese with pasta and a white sauce — it’s over the top. I also used to make this dish that was essentially clams and linguine. We used to have all the broodstock [mature shellfish used for breeding] quahogs. When we were done with them we were like, “okay, we have to eat these.” A guy who used to be the secretary of the Shellfish Group used to call me “Spawnmeister.” So my recipe was called “Spawnmeister’s Delight.” It called for a dozen spent quahogs — we would use the broodstock after they spawned.

BDL: What are you up to now, apart from your continued work with the Shellfish Group?

RK: I am a gardener. That’s part of why I like the aquaculture thing. Even to the point where young shellfish are called seed and you are basically planting them, letting them grow, you are battling diseases and then harvesting the fruits of your labor. I have a few fig trees. It’s been one big experiment. I started out with just a few, but now it’s a little out of control — I have about twenty-five of them now. I have a few outside that I wrap to protect them from the weather. I have one that lives in the sunroom, and that’s the one that really produces. I got like seventy figs off it last year. Fig trees are a little bit of a challenge, and I like a challenge. Plus, a freshly-picked fig is a pretty amazing piece of fruit. When you think about the heart of civilization in the Mediterranean, it was all figs and olives and everything, so it has that kind of historical allure to it. I also have blueberries and apple trees.

I think anybody that’s involved in any kind of aquaculture, a lot of them have gardens and are intimately connected with the land. They live off the land. That’s another thing we are really losing here, but there are still a few people that are holding out and doing things the old way.

BDL: What is something that excites you about the future of shellfish aquaculture on the Vineyard?

RK: One of the most important things the shellfish group has done is help get the private oyster growers going on their farms. That’s one of the things I am the most proud of. The idea that you have private growers spending all their time taking care of all the oyster seed that’s grown at the hatchery — millions of oysters — the success rate and survival rate for that seed is going to be so much better. It’s just great to see people getting into shellfish again. You used to be able to count the number of oyster farmers on the Island on one hand, but now there’s a waiting list for folks who want to start their own farms. I think that’s going to be a huge economic and environmental benefit to the island. The idea that you have local people making a living off shellfish, a local resource, is important. And with the nitrogen issues we’re having, it definitely seems like shellfish are a broad solution to a lot of issues we face as a community.

Want to read more? Check out our story, What’s So Bad About Nitrogen?