Profit and spectacle with conservation on the side?

In 1902, two of the last female passenger pigeons in the world escaped from their pen in Woods Hole, Mass. and vanished. Their captor had been Charles O. Whitman, an influential zoologist and the founding director of the Marine Biological Laboratory, who shipped a flock of research birds to New England every summer from his professorial perch at the University of Chicago.

With two pigeons lost in the woods of Cape Cod, and another packed off to the Cincinnati Zoo, Whitman was left with thirteen birds, a baker’s dozen plucked out of the billions that once darkened the skies of North America. As the remaining pairs laid nonviable eggs, hatched weakly-developed young, and died of tuberculosis, the professor’s flock dwindled. By 1907 all that remained were two hybrid males, infertile, their lineage crossed with that of turtle-doves.

Luckily, there were a few passenger pigeons left in Cincinnati, including an elderly pair named George and Martha Washington. Martha was the product of captive breeding, having hatched at the zoo in 1885, and the zookeepers worked hard to carry on her lineage, even taking her eggs to be incubated by other species.

But the effort was too late — there had been no coordinated program to maintain passenger pigeons in captivity while the species was still abundant. Martha, eventually the last of her kind, perished.

To be fair, the Cincinnati Zoo had other priorities. With hundreds of animals and only $96 in cash on hand, it had gone into receivership in 1898, and it rode a financial rollercoaster for decades. Its purpose was to attract people, not to save species, and to that end the zoo’s leadership employed a range of inventive, if not always successful, strategies. At various points in its early days, the zoo kept and sold domestic dogs, including a Newfoundland, a St. Bernard and a few Great Danes, took in retired circus elephants (including one that was shot for misbehavior and served as steak to guests at the Palace Hotel), hosted boxing matches between a man and a kangaroo, and eventually became home to the Cincinnati Opera. Children rode tortoises like ponies.

With two pigeons lost in the woods of Cape Cod, and another packed off to the Cincinnati Zoo, Charles O. Whitman was left with thirteen birds, a baker’s dozen plucked out of the billions that once darkened the skies of North America.

“There’s only one thing that zoos are about, and that’s recreation,” said Nigel Rothfels, a historian at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee who studies the origins of the modern zoo. “It’s the fundamental reason. If people didn’t go, if people didn’t think they were fun, there would be no zoos.”

“You can look at zoos in the 19th century, and no one uses the word conservation,” said Rothfels. Even as concern about extinction mounted, zoos were seen more as filing cabinets of scientific curiosity than as gene pools for restoring species.

Although their missions have evolved considerably, and today we’re likely to associate zoos with education and wildlife biology, tensions remain and often boil over — between entertainment and conservation, between the spectacle that exotic animals provide and the basic rights and moral agency that many people argue they deserve.

Some recent incidents where zoos have found their feet (and hooves) in hot water include the killing of Harambe the gorilla in Cincinnati and the public dissection of a giraffe in Copenhagen, which both triggered immense public backlash. Rothfels alerted me to a recent incident where a brown kiwi, a flightless, nocturnal bird, was being rented out by the Miami Zoo for aggressive petting and selfies with visitors under bright lights. The kiwi encounter was halted after receiving wide condemnation from the citizens of New Zealand, where the bird is a national symbol. “This was not well conceived,” a spokesperson for the zoo admitted on a New Zealand radio program, as thousands of human kiwis listened in.

To make matters worse, this particular bird, named ‘Paora’ after a Maori environmentalist, had hatched in Florida as part of a captive breeding program to help recover the endangered species. As one of only a few hundred kiwis living in zoos abroad with the blessing of the Maori and the New Zealand government, its treatment rose to the level of a diplomatic incident.

Incidents like these are sparks in a tinderbox of concerns about whether we should keep animals in captivity, and how they should be treated when we do. Once ignited, the whole debate goes up in a roaring blaze.

And for nearly as long as there have been zoos, people have been worried about the animals inside them. “From the middle of the 19th century on there has been pushback about whether they’re cruel places,” Nigel Rothfels said. “And that pushback has made zoos better.”

“People sometimes ask me, should there be zoos? And my answer is usually something like, well, there have always been,” Rothfels told me. He pointed out that “substantial collections of unusual animals” have been around since antiquity, for as long as people have been organized into societies with divisions of labor, leisure time, and urban centers.

And for nearly as long as there have been zoos, people have been worried about the animals inside them. “From the middle of the 19th century on there has been pushback about whether they’re cruel places,” Rothfels said. “And that pushback has made zoos better.”

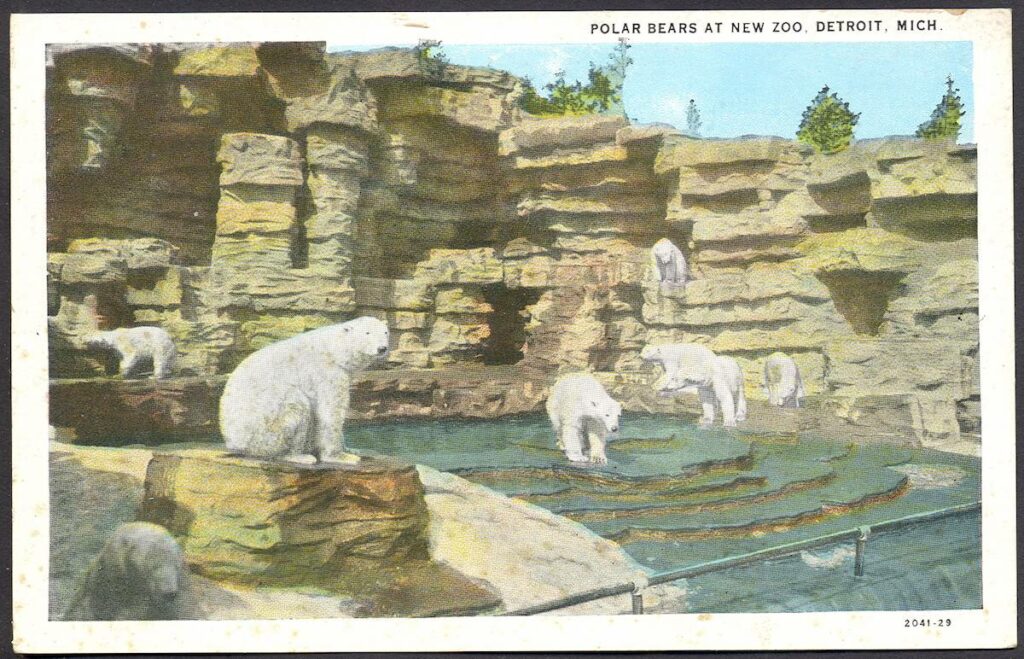

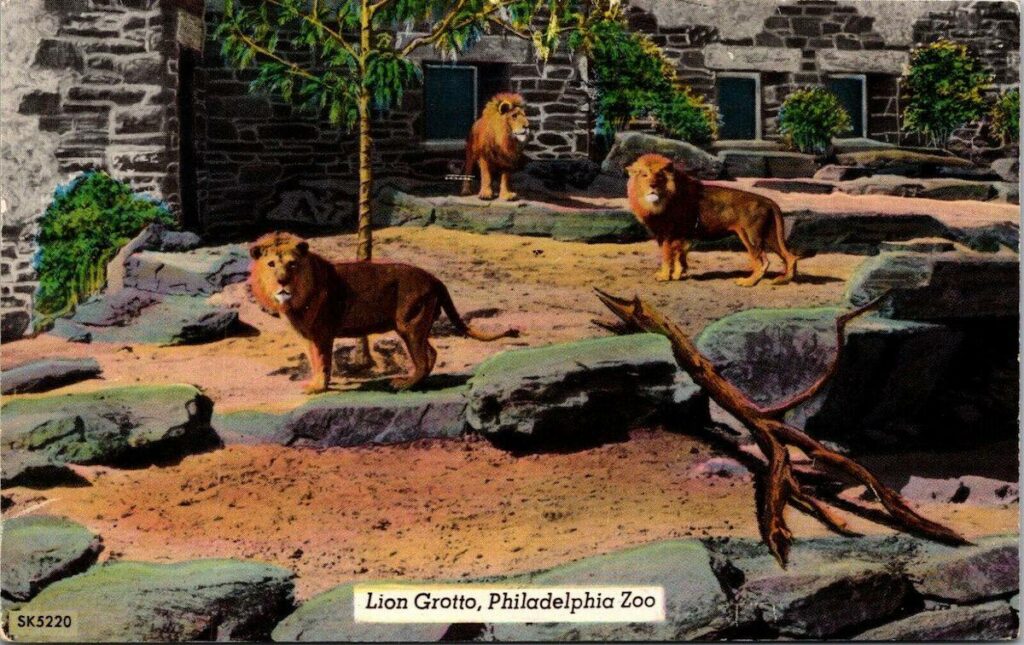

Zoos have incorporated people’s inherent discomfort about the treatment of animals into more sophisticated and naturalistic exhibits, starting with a German entrepreneur and animal dealer named Carl Hagenback. “He’s the one who recognizes that at the end of the 19th century, people are really uncomfortable with the idea of animals behind bars, animals in cages, animals being treated badly,” Rothfels said. “Many people who visit zoos in the late 19th century are talking about the smells, are talking about how the animals don’t look healthy.”

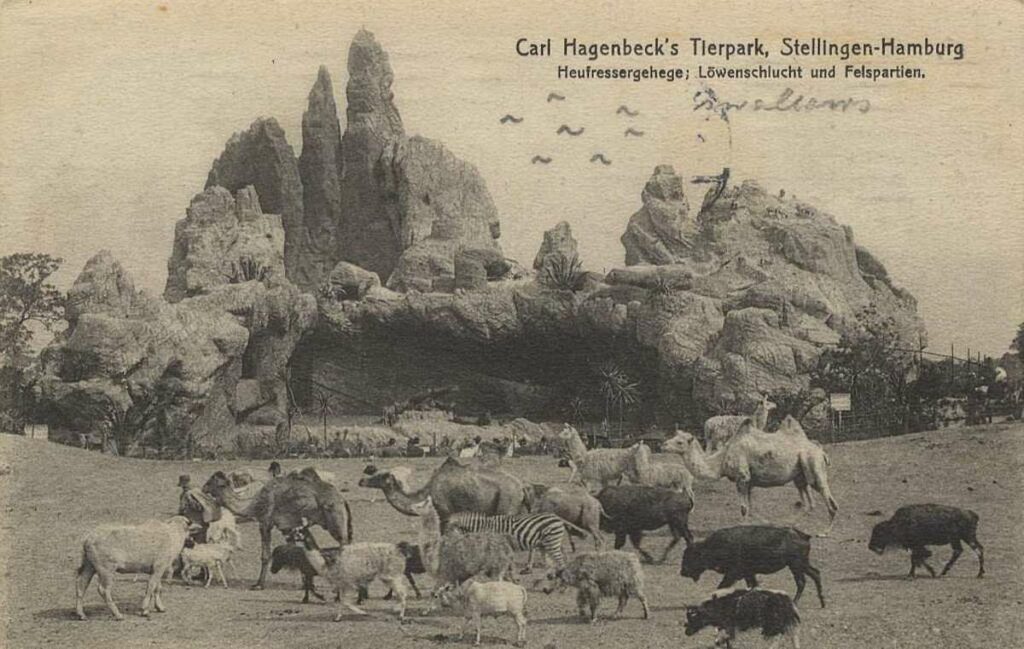

As Rothfels recounts in his book, “Savages and Beasts: The Birth of the Modern Zoo,” Hagenbeck created an enormous animal park, the Tierpark Hagenbeck, in Hamburg, moving more than a million cubic feet of soil and making his own spur on the local railroad. Rather than bars and cages, Hagenbeck designed scenic habitats separated by cleverly built ‘natural’ features and carefully placed moats, which in panorama gave the appearance of a unified landscape, with predators and prey shown together in deceptive peace.

Hagenbeck’s park was a sensation when it opened in 1907. “He creates these landscapes which are better than nature itself,” Rothfels told me. “He helped people believe that zoos could be nice places for animals.” Hagenbeck began to portray his project not as the warehouse of a commercial animal broker (which it was) but as an ark, a sanctuary for wild animals away from the violence of nature and the depredations of humankind.

The Tierpark Hagenbeck still exists, with many of its original exhibits intact, and its illusory, naturalistic style of display is largely the one we encounter at zoos today. “Zoos make themselves more and more like our fantasy of a wild space,” Rothfels said. “The technology’s getting better. The soundscapes are getting better. There’s a rainforest in Vienna’s Zoo where you better find a big old leaf to stand underneath when the rain hits, because you’ll get completely drenched.”

Hagenbeck’s influence spread, both as a trendsetter for zoological parks (he helped redesign the Cincinnati Zoo in the same fashion) and as the most powerful animal dealer of his era, through whom many American zoos competed to acquire their animals.

He had access to some of the rarest and most prized creatures on earth, and even better, “he was cash on delivery,” Rothfels said. “So you don’t pay if the animal doesn’t show up alive. And if it died within a reasonable time, he would say, ‘Oh, I’ll just replace it.’” It was a bloody business, with mothers routinely killed to acquire their docile young, and high mortality on the long journeys to unfamiliar climates.

Hagenbeck relied on an extensive network of animal catchers, and their operations relied in turn on the extensive colonial projects of the European powers, whose grasping outposts reached to the far corners of the globe. In the early 20th century, the Smithsonian National Zoo would sometimes take a similar approach, asking diplomats and officers in US-occupied places like Panama and the Philippines to acquire live animals wherever possible.

Zoos’ no longer function as for-profit animal dealers, and they have mostly stopped capturing animals from the wild, but the core spectacle remains. As zoos evolved from the menageries of the distant past into the civic institutions of the late 19th and 20th centuries, they became woven into the fabric of public life, increasingly at pains to demonstrate a public mission beyond mass entertainment.

“Right around the beginning of the 20th century, people start using the word ‘conservation,’” Rothfels told me. “And the key person there is William Temple Hornaday.”

Hornaday, a taxidermist and zoologist, helped found both the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and then the Bronx Zoo, and went from skinning and stuffing bison for posterity to collecting live specimens and facilitating their successful reintroduction in the wild.

But this early conservation, successful though it was in some cases, came packaged alongside an obsession with purity and evolutionary hierarchy that scientists at the time applied to both animals and people, species and races. Hornaday placed a Congolese man, Ota Benga, in the primate house at the Bronx zoo, to the moral outrage of New York’s black pastors, who boycotted the zoo. Madison Grant, a co-founder of the New York Zoological Society and the Bronx Zoo and a close friend of Teddy Roosevelt, wrote a tract on eugenics called “The Passing of the Great Race” that Adolf Hitler later referred to as “his bible.”

Even before the eugenics movement came to dominate scientific discourse in the early 20th century, zoos had realized that exhibiting so-called “primitive” people could draw big crowds. Hagenback placed Indigenous peoples alongside wildlife in various settings at his zoological park, and in Cincinnati the zoo exhibited nearly one hundred Sioux, who lived in a facsimile village there for several months.

Just as these exhibits of human beings provided fodder for the public’s lurid imagination about the hierarchy of mankind, so ideas of racial purity informed scientists’ vision of what a species should look like and how it should be restored. In a TED video, Rothfels recounts the tale of the takhi, or Przewalski’s horse, which was reintroduced into the steppes of central Asia after decades of captive breeding. Because many of its breeders had never seen this horse in the wild, and because the provenance of the original stock was so uncertain, they selected for traits that they assumed a “pure” takhi should have, meaning that the species may have been bred to match the imagination of its keepers more than the variability of the species as it once existed in the wild.

To make things more complicated, the San Diego zoo recently cloned the takhi from the cryogenically preserved cells of a stallion that died in 1998, producing two new stallions that the zoo hopes will restore some genetic diversity to the dangerously inbred population.

The biblical ark, having two of each animal, is not a recipe for continued species viability. Wild populations require a healthy mix of genes, and animals also learn from each other, build social structures, form specialized subpopulations, and pass down epigenetic variations to their underlying genetic code — so much so that you could argue that these contextual, environmentally-specific traits are part of what make a species unique.

It’s not clear that the passenger pigeon, had it been bred successfully before going extinct in the wild, would have been able to repopulate its former range, given all the other changes in North America’s wild landscapes then and since. And it’s not clear now that species like the Florida grasshopper sparrow or the red wolf of the American Southeast will recover absent significant improvement in the conditions that brought them to the brink.

But these efforts do buy time. Zoos’ modern focus on genetic diversity and minimum viable populations, with decisions made using cooperative Species Survival Plans, has made headway for California Condors, Black-footed ferrets, and Arabian Oryx, among other animals (although the ultimate recovery of these species still depends on addressing the underlying causes of their decline). Zookeeping has also led to important developments in wildlife veterinary medicine, which can improve conservation efforts for populations in the wild and provide insights into the detailed minutiae of animal biology that researchers would have a hard time accessing in the field.

Zoos, many conservationists argue, are a form of triage in the face of cascading ecological catastrophe in the outside world. Aligned more than ever with the field of conservation biology, itself a relative newcomer in science, zoos are also devoting money to protecting species in situ, and to ensuring the ongoing viability and diversity of the broader wild landscapes in which those species dwell.

At the same time, protected areas like national parks increasingly behave more like zoos, with biologists closely tracking and supervising animals, providing medical care, and drawing strict boundaries that restrict freedom of movement and natural migration.

“They’re going to be managed in the same kinds of ways zoos are,” Rothfels said. “Identifying who is breeding with which, and taking out individuals that need to be translocated. And so the world ends up looking much more like a bigger zoo.”

In any case, Rothfels pointed out, the fraction of zoos’ actual day-to-day activity and budget devoted to substantial conservation work is small, often out of proportion to their claims; much of the most significant work in the field is done by a few large institutions, like the Bronx Zoo (and its parent organization, the Wildlife Society) or the Monterey Bay Aquarium. The remaining resources are devoted to zoos’ historical purpose: drawing a crowd.

One zoo employee, quoted by sociologist David Grazian in his book American Zoo: A Sociological Safari, bemoaned the extent to which her institution had become like Chuck E. Cheese, with claw-machine games in the cafeteria and a bouncy house almost every weekend. “We have the moon bounce all the time,” she told Grazian. “‘The moon bounce is here! The moon bounce is there!’ What the heck?”

And that’s not to mention the effects of captivity on the animals themselves. As research pours in about the sophistication and mystery of animal minds, it becomes increasingly fraught to keep and exhibit them, no matter how much we strive to disguise the nature of their captivity.

“Zoos cannot but disappoint,” wrote the critic John Berger, whose essay “Why Look at Animals” is inevitably encountered by people researching this topic. “The zoo to which people go to meet animals, to observe them, to see them, is, in fact, a monument to the impossibility of such encounters.”

In some ways, zoos are better for studying Homo sapiens than wild animals: They reflect and refract our desires for connection with nature, with animal intelligence, and with pre-history. How zoos move forward depends in part on these desires.

Some zoos are accredited — an industry standard, but a standard nonetheless. “There are some things in that accreditation that really count,” Rothfels said. “Do you have onsite veterinary care? Do you have people with actual expertise here who know things? Or is it just somebody you hired to throw meat to the lions? Is there an actual education program? Is there a good perimeter fence? Do you have financials which make it clear that your institution will be able to survive through difficult times and not just turn your animals loose?”

And “turning loose” zoo animals is no easy task. Many zoo animals are emotionally troubled as a result of their lives in captivity. Others have become overly acclimatized to people, losing their fear of human beings and, in some cases, developing strong emotional bonds with their zookeepers. Circumstances such as these make a truly ‘wild’ life for them, whatever we take that to be, forever out of reach.

Rothfels takes the long view. Zoos are likely to stick around for the foreseeable future, he thinks. But “pushback has made zoos better,” he told me. “Animals live longer. The quality of their life is better. There’s more attention to their mental needs.”

“If it were me, I would have many fewer facilities, much more regulation,” he said. “Fewer places that were much better. But that’s not the way this country runs, right? State by state, the regulations are so different.”

In some ways, zoos are better for studying Homo sapiens than wild animals: they reflect and refract our desires for connection with nature, with animal intelligence, and with pre-history. How zoos move forward depends in part on these desires. Do we prefer a deeper illusion, to immerse ourselves ever more convincingly in a facsimile of animal life in the wild? An old-fashioned, profit-seeking enterprise of spectacle and comic relief? Or something else, something new?

“The single thing that I want of zoos is that they ask themselves tough questions about why it is they’re doing what they’re doing,” Rothfels told me.