Islanders are hard at work conserving Martha’s Vineyard’s Great Ponds — what exactly is at stake?

What is a great pond?

I know, you know. A nice big pond on the coast of Martha’s Vineyard. Brackish, surface glimmering and tame, dune-sheltered against a roaring south shore ocean. Its coves reach like fingers northward, their pinched ends holding still water. Home to osprey, otter, eelgrass, artist. Site of Island rituals: the opening of the cut, the catching of the bass, the long walk to the beach.

But what the hell is a great pond, technically? I’ve lived on the Vineyard, spoken with experts, and looked in history books, and I’m only getting more confused.

The ponds that bear the title — the Edgartown and Tisbury Great Ponds — come first to mind. Another criterion for their “greatness” might be how much of the Island they cup in their palm, and these two together drain about 30% percent of the Island’s land area — they receive more water than what flows into the sea.

But Paqua Pond is a great pond, too. It covers 14 acres in Edgartown, around 60 times less than its largest neighbor. Its watershed includes its immediate surroundings and little else.

As I look, there are 16 ponds on the Island that are recognized as great ponds by the law of the land, which happens to be a short list maintained by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Quality.

The list includes more ponds and coves on the South Shore. Together they resemble outstretched hands, palms down on the salty southern barrier beaches and fingers pushing up the frost bottoms of the Island’s great outwash plain. Notably, Quenames and Crackatuxet Coves don’t make the list.

Menemsha Pond, though indisputably one of the greatest Island ponds, is not technically a great pond. Crystal Lake in Oak Bluffs might be better labeled a soup than a pond, going by recent water quality analyses. At 12 acres, it is nevertheless a great pond.

The Code of Massachusetts Regulations says that a great pond is “any pond which contained more than ten acres in its natural state, as calculated based on the surface area of lands lying below the natural high water mark.” But snubs are handed out to several ponds that seem to be over 10 acres au naturale.

In my effort to clarify the criteria, I became entangled in a fairly circular email exchange with the DEP’s Waterways Program. My article “should not try and ‘interpret’ the regulations or make any assessments of why certain ponds are named as Great Ponds vs. others,” they instructed me. In fact, they wrote, “DEP also does not ‘interpret’ the definition. Any pond that meets the definition of a Great Pond is a Great Pond.”

They also categorically stated that “great ponds are not tidal waterbodies.” I had a hard time not “interpreting” this one, since Oak Bluffs Harbor and Farm Pond are certainly so, and several others are tidal periodically, when their connection to the sea is restored.

In 1996, when the state went county-by-county and made this list, it was by its own admission not an exhaustive effort. New water bodies can be added via a “request for determination of applicability.”

Semantics aside, why does it matter what a ‘great pond’ is? The conversations around these ecosystems often refer to them by other categories, as estuaries, embayments, coastal ponds, or kettle ponds. The Massachusetts Estuaries Project, a regional effort to conserve these places, includes ponds you might have been skimming this article for in vain — Tashmoo, Lagoon Pond, and Sengekontacket get their due here, as does Menemsha.

Well, the title of ‘great pond’ does carry legal weight, enshrined in law with remarkable continuity since the colonial ordinances of the 1640s, before the Vineyard was even part of Massachusetts. Ponds over 10 acres remain in the public trust, and “shall be free for any man to fish and fowl there, and may passe and repasse on foot through any mans [sic] property for that end.”

The question of what you can do with your right to this trust has been hotly litigated — in an important case in Fall River in 1888, it even split the opinions of famous friends and future Supreme Court justices Louis Brandeis and Oliver Wendell Holmes.

Often in question was the effect of textile mills, dams, and public water supplies on other pond users. In 18th century Fall River, a soap company on the town’s great ponds spent twenty years boiling dead horses and cows and pouring the results into the public trust. Judging by the public’s olfactory response, their trust had been violated.

Other 1800s cases were actually about ice — who can cut it, take it, and sell it. In West Roxbury, for example, some Jamaica Pond residents, “without permission, and in the face of express prohibition from the town, proceeded to cut and carry away ice as merchandise.”

In 1863, the court responded with a delightfully expansive list of public rights on the great ponds, which included: “Fishing, fowling, boating, bathing, skating, or riding upon the ice, taking water for domestic or agricultural purposes or for use in the arts, and the cutting and taking of ice.”

People on the Vineyard used to exercise their ice skating rights a lot more. One account claims that, because the south shore ponds used to be more connected by open water, you could travel on blades of steel alone from the Tisbury Great Pond to Edgartown, or from Long Point to Chilmark Pond.

From that perspective, what makes a great pond great might be its outsized role in the nature and culture of the Island — as a place where people and creatures gather, where the small Island meets the infinite sea, and where the processes of change that shape sand and life march relentlessly forward.

Ecosystems in flux

At seven o’clock on a glassy morning, in the garden-fresh air after a rainy night, Julie Pringle (Bluedot’s spring Local Hero) is nosing a small boat up to a sandy landing on the Edgartown Great Pond. Although it’s June, the pond is quiet — the buzz of outboard motors and landscaping equipment dormant for now.

Preparing to hop in, with bags and boxes of gear, are Emily Reddington and David Bouck. With Pringle, they’re taking the most comprehensive water samples of the pond to date: several times a week, all summer long. Their organization, the Great Pond Foundation, was created to conserve this pond, but their monitoring programs and advisory help have expanded to the Tisbury and Chilmark ponds too.

“This is the biggest of the ponds we sample,” Reddington said, “and it’s also the longest running, so we have more of an intimate knowledge of it.”

We’re on the water to get a snapshot of how the pond is doing. Not only whether it’s safe for people — a primary concern for everyone involved — but whether it’s supporting the wider network of life that depends on it. At their best, these ponds are hatcheries, nurseries, enclaves, and buffets, depending on your place in the food chain. At their worst, they can become toxic for people and animals, a severed link that snaps the whole chain loose.

The health of the great ponds is the subject of great interest and strong opinion. In these waters, I am learning, science is a crucible on which Yankee folk wisdom can die or be reborn.

A surprising amount is reborn. Andrew Jacobs, who manages the Wampanoag Environmental Laboratory in Aquinnah, told me, “There are so many people who are so in tune to this Island. They don’t realize how important their observations are. What they’ve seen, what they’ve told us, we’ve been able to confirm through scientific analysis.”

Sure, some notions, like the idea that waterfowl are the main source of nitrogen in large ponds, don’t hold up to isotopic study. It’s easy to speculate until a team of world class scientists shows up. After that it’s numbers, more numbers than you had maybe hoped to see.

The numbers involve nitrogen, phosphorus, salinity, dissolved oxygen, phytoplankton, and real estate.

They show up in emails, then maps and beach closures, then reports, then planning meetings, town meetings, and then lawsuits. But first, they arrive aboard a small outboard skiff on one pond or another, often tapped into a purple iPad owned by the Great Pond Foundation.

The Foundation is not alone in this work. The Martha’s Vineyard Commission takes their own periodic read on the ponds, and Jacobs and his colleagues at the Wampanoag Environmental Lab not only study up-Island water bodies but process water samples for almost everyone else on the Island.

Jacobs works with data from Menemsha and Squibnocket that goes back decades. “There’s a bunch of different ways that you can look at the same data set to try to understand what the health of a water body means,” he told me. “We do all of our analysis here in house. Bacteriological, dissolved oxygen, temperature, salinity, conductivity.” They study how this data “relates to not only environmental health and human health, but how it relates to the health of sustenance foods and resources.”

These ponds are immensely productive when the balance is right, and in good years sustenance can include herring, quahogs, and scallops among many other foods long accessed by Wampanoag people. In years where excess nutrients wash and plume from human settlement into the water, what flourishes are frenzies of phytoplankton, microscopic marine plants that bloom and quickly die, depriving the water of oxygen, blocking sunlight, and sometimes producing very toxic compounds.

We’re on the water to get a snapshot of how the pond is doing. Not only whether it’s safe for people — a primary concern for everyone involved — but whether it’s supporting the wider network of life that depends on it.

A great pond thrives as a meeting of land and sea — too much of one or the other and it leaves the zone where its characteristic species do well. Pringle describes the pond like a sommelier. “We prefer it to be on the saltier end,” she says, taking a meter reading in parts per thousand. “This is 16, which is brackish. The ocean is about 34, freshwater zero. So we’re really right in between.”

“We’d love to see dissolved oxygen above six milligrams per liter,” Reddington added. “Those are the EPA standards, those are the Mass Estuaries Project standards. Once you start to get below that, down to about four, that’s not ideal. Certain things will have to swim out of the area. Once you’re below two, that’s where it’s critical. If you get between two and zero, it’s bad.”

For a layperson, here’s an indicator of how a pond is doing: “If you can see down most of the year to three meters, that’s a good thing,” Reddington said. Clear water means less organic material is clouding things up, which means that excess nutrients like nitrogen haven’t been spurring their runaway growth. It also means eelgrass, a cornerstone species in this pond, has enough light to grow in the deeper, cooler water.

The Edgartown Great Pond has more eelgrass than you might expect. It’s been on a rebound, enough so that visiting scientists are surprised that the numbers add up. “For the amount of wastewater coming in, we should not have the grasses that we do,” Reddington said.

These submerged aquatic meadows are a boon for biodiversity, carbon sequestration, and water quality. The eelgrass improvement in the Edgartown Pond is a testament to judicious use of the Island’s most readily available management tool — the cut.

Opening a coastal pond to the sea allows a salty flush of the whole system. It’s a tradition dating back to the hand-dug cuts made by the Wampanoag (the cut on James Pond is still dug this way). When I went out in late June, the opening on the Edgartown Pond had recently closed, naturally sealed by the movements of sea and sand.

“We always get excited when we have a long successful cut because then the salinity goes up into the 20s,” Pringle said. “Didn’t quite get up that high, but it’s 16 right now.”

“Better than where it was before,” said Reddington. It had been eleven and a half, very near the lower limit at which eelgrass can survive.

By taking water samples precisely and often, the Great Pond Foundation can observe the changes wrought by these brief openings in granular detail. “If the cuts didn’t happen, this pond would not be nearly as healthy as it is,” said Reddington.

The timing of a cut is a delicate dance. Reddington said, “It might benefit water quality and eel grass but it might not be the ideal time for spawning herring to get in and out.” Or maybe the pond is high enough, and the ocean low enough for a strong cut to form, but other factors aren’t ideal. “Which things do you optimize for? To do it well takes a lot,” she said.

Opening a coastal pond to the sea allows a salty flush of the whole system. It’s a tradition dating back to the hand-dug cuts made by the Wampanoag — the cut on James Pond is still dug this way.

As we neared a patch of eelgrass that’s been expanding steadily since 2016, Reddington attributed its growth to “a general reduction in nitrogen, but also an increase in the flushing capacity with each opening, with consistent dredging and well-timed openings. The combination of the two gets that flush up into the coves more consistently.”

Lest it be said that eelgrass doth great pond make, many of the other ponds don’t have it — either because of water quality or relative freshness; some are just different habitats.

Tisbury Great Pond has a stronger freshwater influence on account of the Tiasquam River and Mill Brook, said Bouck, something of a pond sommelier himself. “You’ve got these two tributary streams that start in Chilmark and travel all the way down through this watershed.” Throw in more agriculture, no town sewer system, and all the other variables that make it unique, and you’ve got “roughly the same size pond, roughly the same area of watershed but very different inputs,” he said.

Edgartown Great Pond has few natural streams of any size, so it’s mostly groundwater coming in. Even so, Pringle added that “Edgartown used to be a fresher pond, back when there was a herring fishery. Herring like freshwater, and now it’s more managed for the shellfish and the eel grass.”

Coastal ponds with less ocean influence have a harder time coping with excess nutrients. For example, Jacobs at the Wampanoag lab told me, “Menemsha is a reasonably healthy pond. Squibnocket on the other hand, is not. It’s really struggling.” The only refreshing dose of salt water comes to Squibnocket from a single culvert to Menemsha pond, and the occasional overwash of its ocean-facing shores. It suffers from poorer water quality as a result, and has already had harmful cyanobacteria bloom watches issued this summer.

So each pond has its own balance sheet — nutrient inputs balanced against how often the pond is flushed, its size, its expected cultural use, and many other factors. The research part is just making sure we can read the sheet.

Remembering the greats

At the heart of all this monitoring work, and the restoration and management that follows, is an attempt to reckon with change. Some of it is inevitable, sure, like the flow of tide and sand that’s pushing the south shore north.

Other kinds of change threaten to further unravel the qualities that made the Island worth living on in the first place: sites (and sights) of almost unimaginable richness.

Bouck, Watershed Outreach Manager at the Great Pond Foundation, said, “my parents remember a time when they could canoe back and forth between Tisbury Great Pond and Long Cove Pond.”

He grew up on the Tisbury Great Pond, and these days he’s thinking a lot about memories, because he’s in the process of preserving thousands of them from Islanders who have their own tradition of keeping an eye on things.

“They’ve been recording data, in many different forms at many different times for their entire lives,” Bouck said. “So you just have this massive data set around that pond, just due to the culture of the area. But a lot of it exists in journals or notebooks or handwritten spreadsheets, observations, poems, photos, or just in their opinion.”

What makes a great pond great might be its outsized role in the nature and culture of the Island — as a place where people and creatures gather, where the small Island meets the infinite sea, and where the processes of change that shape sand and life march relentlessly forward.

Using a grant from the Martha’s Vineyard Community Foundation, he’s digitizing one of the Island’s longest running citizen science projects — decades of water monitoring data from riparian owners and other Islanders on the Tisbury Great Pond.

The project began in collaboration with the late Kent Healy, civil engineer, water-quality aficionado, pond commissioner, and West Tisbury selectman, whose meticulous records of hydrology on the Tisbury Great Pond spanned decades. After Healy suddenly passed away last October, the project gained more urgency.

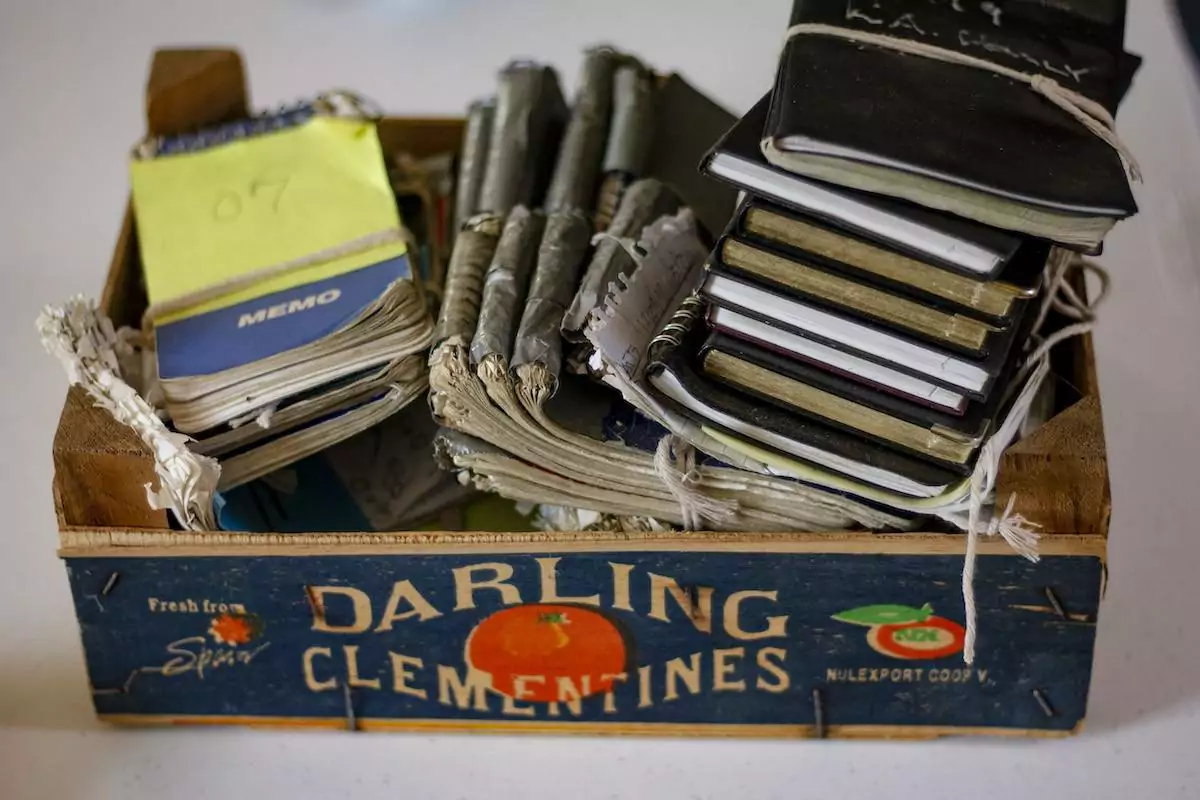

“It kind of turned into, ‘Okay, we need to first of all get in and preserve everything that he ever did,’” Bouck said. He’s nearly finished digitizing the main records. “We figured out it’s about 30 minutes per book,” he said. “And there are 60 books.” He produced a box of worn notepads, crammed with details of rainfall, pond height, and stream flow.

“I’m the wind, rain and gravity guy,” Healy is recorded saying in Ollie Becker’s new film, On Our Watch. He goes on, “You want to know what’s going on? Measure the rainfall, measure the flow in the brooks, measure the elevation of the pond, measure the groundwater. Keep track of stuff.”

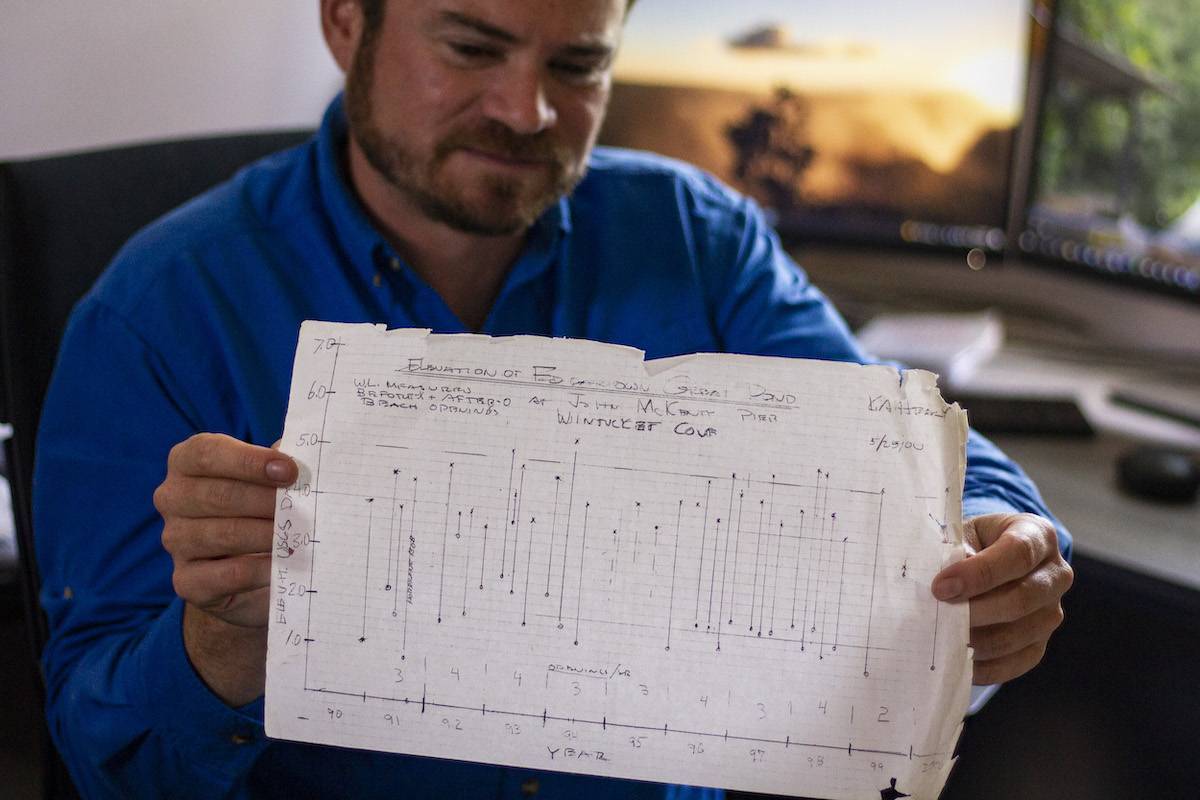

The late John MacKenty was another Islander who collected pond data, recording elevation consistently from his dock on Wintucket Cove on the Edgartown Great Pond for more than 30 years. His data was incorporated into local and state management “because it was the best data set that was here,” said Reddington. MacKenty’s son, Ed, has carried on the tradition from Wintucket Cove, this time with real-time digital monitors provided by the Foundation.

This multigenerational tradition of keeping vigil on the ponds is one of the only glimpses we have at whatever the ‘natural state’ of these ponds has been over the years.

Reddington said, “It’s continuing traditions, it’s keeping the data alive and it’s the community working together to help the ponds.”

About the Edgartown Great Pond, she said, “generations of people have cared about this pond, which is one of the reasons it’s turned from something that was pristine into something that was struggling with regular algal blooms into something that’s now considered a restoration success story. The work is not done here.”

There are solutions to what’s afflicting the great ponds, and hopefully the will to tackle them, too. Conserved land, carefully managed development, and clever septic all have some role to play.

As I found when I sought answers in the official list of great ponds, not a lot of Vineyard ponds technically make the cut. Fortunately for those who live here, the cut is one thing that Islanders are very good at making themselves.

What You Can Do

Click here to learn how to preserve our great ponds.

Editors’ note: Artists on Martha’s Vineyard have been capturing the beauty of the great ponds for centuries, helping us see what is so valuable and why we must work to save our ponds. See our “Art of the Great Ponds” slideshow, sponsored by Martha’s Vineyard Bank. MVBank is sponsoring a show, “The Art of the Great Ponds,” at their Chilmark branch, from Aug. 12 to Sept. 1, with an opening at 5 pm on Aug. 12, featuring art from the Martha’s Vineyard Permanent Art Collection, curated by Monina von Opel. Here’s more info.

Sam Moore will continue his investigation into Martha’s Vineyard Great Ponds with a story on salt marshes in our October issue.