How a little-known center in Woods Hole became a hub for climate research and policy.

Looking at the stately Woodwell Climate Research Center, which sits on a hill off the road leading to Woods Hole, you might not guess that the renowned institution began in one man’s basement.

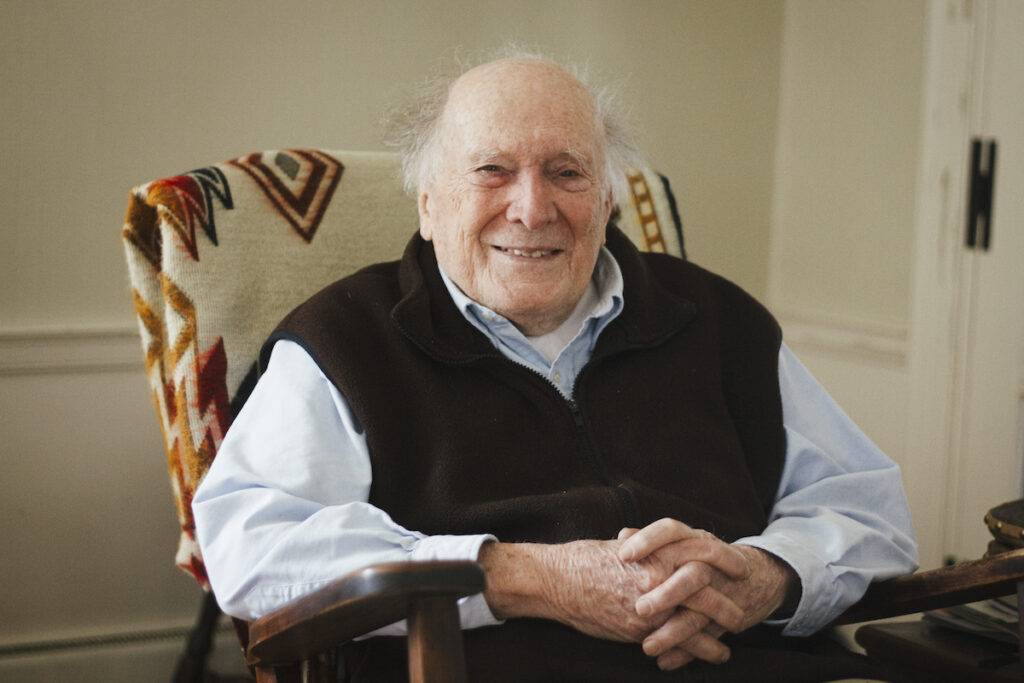

That man is George Woodwell, and since 1985, the center he founded has been deeply involved in climate research and policy at home and abroad. Today, it employs nearly 100 scientists and staff, whose work on everything from permafrost to wildfires is shaping our understanding of the world we live in — and what we’re doing to it.

The Center’s scientists have been lead or contributing authors at the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) since the outset, and in recent years its leaders, including John Holdren and Philip B. Duffy, have been science advisors to the Obama and Biden administrations.

How did these scientists all wind up here, in this hamlet on Cape Cod, which also boasts the Marine Biological Laboratory, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, and the National Marine Fisheries Service? Perhaps because Woods Hole attracts migrating scientists like a duck decoy — many arrive for a stopover, and some get bagged. “It could be, some say, that this is the place to be for a scientist in summer,” the New York Times gushed in 1997.

It’s a hotbed of scientific opinion, and George Woodwell’s take is: “The accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere presents a serious worldwide problem that threatens the stability of climates within the lifetimes of people now living,” and “the time to take steps to mitigate those problems is now.” It’s pretty conventional wisdom — but these words are from 1979. And for Woodwell, it was old news then.

“From my standpoint, we should have just gone hammer and tongs to reduce the buildup of CO₂ in the atmosphere and cool the Earth,” Woodwell, now 93, told me when I visited him at home in April. “And we should be doing that now.”

Woodwell first began worrying about carbon dioxide when it was present in the atmosphere at around 320 parts per million. Today, that number is somewhere around 420 parts per million, and global temperatures have risen by almost 2 degrees Fahrenheit over the long-term average.

Our observations have improved, but the forecast has not, Woodwell says. The center he founded, and the work it continues to do, are at the heart of how climate science plays out in the public sphere.

Masters of Carbon

The origins of the Woodwell Climate Research Center can be traced to the early days of ecology, and to the scientists who worked to understand relationships between Earth and life at the planetary scale.

George Woodwell graduated from Dartmouth College in 1950 and joined the Navy, sailing aboard an oceanographic survey vessel in the North Atlantic. His ship ran back and forth across the newly discovered Mid-Atlantic Ridge, and its crew watched with deep-sounding sonar as the undersea mountain range rose up to meet them.

Off the boat, Woodwell got a doctorate in botany at Duke under groundbreaking ecologist Henry J. Oosting, one of the “old boys of the subversive science” as Woodwell once affectionately called them. After a few years at the University of Maine, he moved to the Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island, where his wide-ranging research laid the groundwork for his move to Woods Hole and all that followed.

Right away, Woodwell embroiled himself in red hot issues like pesticide exposure and nuclear radiation as he set out to understand their effects at an ecosystem scale. He’d begun studying DDT in Maine, collecting soil samples after aerial spraying. In the 1960s, he continued his investigations at Brookhaven, joined by Charles F. Wurster, a young chemist with a keen interest in ornithology.

“We spent a summer collecting birds and fish and mud from the bottom and sediments in the salt marsh,” Woodwell recalled. “We got a spectacular set of data showing not only the DDT in the soils and the fact that DDT was everywhere, but also showing that DDT was accumulating in the living systems of the place.”

Though their findings were published in the rarefied pages of the journal Science, it was Woodwell’s participation in a ramshackle lawsuit brought by a small group of volunteers that stopped the spraying of DDT in Suffolk County.

George Woodwell is a bridge between the origins of the modern American environmental movement and its future, from the now-textbook cases of nuclear radiation and DDT to the ongoing reckoning with climate change.

In 1967, on the heels of their successful injunction against the Suffolk County Mosquito Control Commission, Woodwell, Wurster, and a handful of fellow Long Island “troublemakers” met in a conference room at Brookhaven, where they signed the founding documents of the Environmental Defense Fund. Their work, and the legal strategy the EDF pursued, led to a federal ban of the substance in 1972.

“George was the most respected scientist in the room, and he was always the strongest advocate for maintaining our scientific integrity,” Wurster wrote in his memoir of that time.

But Brookhaven was an atomic energy laboratory, after all, so Woodwell also set up experiments to study the ecological effects of nuclear contamination. Winching a piece of Cesium-137 up and down from a safe distance away, he exposed a forest of pitch pine and oak to ionizing radiation, and observed as the effects rippled out from the source.

Detailed measurements from this “gamma forest” showed zones where all higher plants had been killed, and those where only sedges, then shrubs, then oaks, and furthest out, the sensitive pitch pines, were able to persist. Whether from war, accident, or energy, these were the new risks of the nuclear age. Woodwell wrote in 1962 that this forest and other models “provide at least an understanding of what is happening to the environment, if not the wisdom to control it.”

Woodwell remembers his stint at Brookhaven fondly for his freedom to design and conduct basic research alongside supportive colleagues and administrators. “We had a wonderful Institute of Ecology, we could do anything, I could build anything, I could design anything,” he recalled. And so he designed all kinds of ways to measure the dynamics of the ecosystem around him, and also to measure carbon dioxide.

“We built all kinds of equipment for measuring the metabolism of a forest,” Woodwell said. Their new equipment took precise readings of photosynthesis and respiration from leaves, branches, stems, bark, and roots. “So that was very exciting, to be able to take what we called an ecosystem apart, and watch it through a whole day or a month or a year or longer.”

Woodwell said, “That was when the issue of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was first beginning to appear on the front pages of newspapers, and also appear in the scientific literature, as Dave Keeling at Scripps built up a record showing the year-by-year accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, a beautiful record which was his life’s work.”

Richard A. Houghton, a scientist who spent his career working alongside Woodwell from their days at Brookhaven through retirement from the Woodwell Climate Research Center, told me, “George had the foresight to really think that climate was going to be an issue because we were putting a lot into the atmosphere.”

Most of the people doing global carbon math at the time were oceanographers and atmospheric scientists, Houghton said, “and they had no idea what land was doing.” As ecologists with a particular interest in botany and terrestrial systems, Woodwell and his colleagues at Brookhaven began trying to detail the carbon absorbed and released in the biosphere.

And not just in forests. They drew detailed diagrams of how carbon moves around in Long Island marshes, tracking the flow of organic matter among the cascading relationships of life in the tidal world. It was carbon accounting, a set of equations they could extrapolate to a planetary scale: this much in, this much out.

“We were masters of carbon,” Woodwell said.

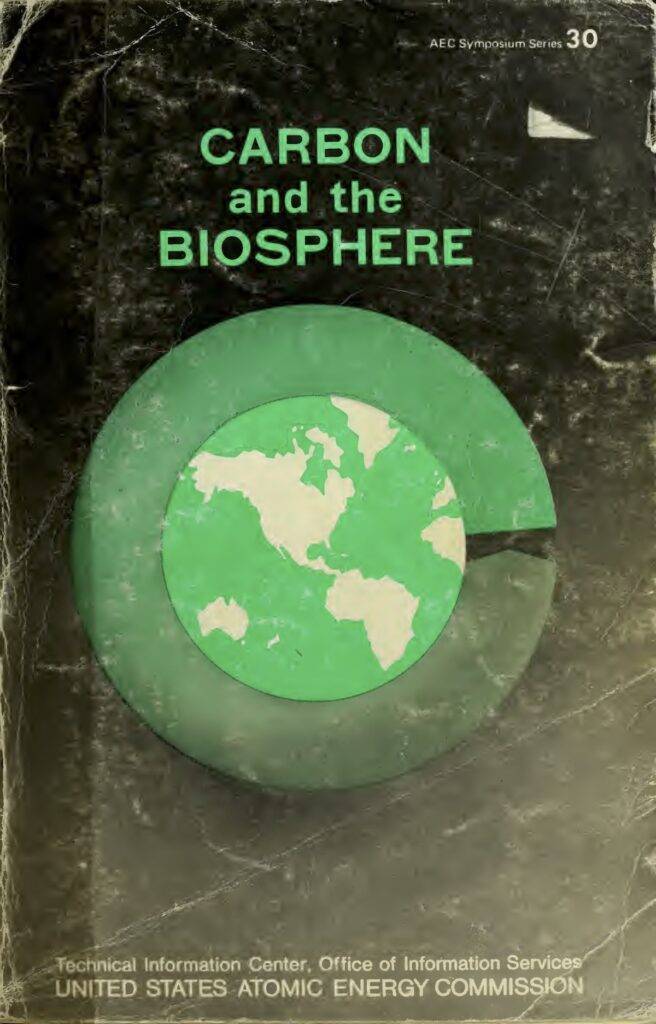

In 1972, Brookhaven hosted a hundred scientists for an appraisal of carbon in the biosphere. The proceedings of this conference, edited by Woodwell, began with a stark premise: “The change that man is making in the world carbon budget is among the most abrupt and fundamental changes that the biosphere has experienced in all of world history. The change is in the stuff of life itself and is by now common knowledge.”

Tasked with describing the consequences of this change, and armed with only an inkling of the processes at work, the scientists asked: “Why has the change not been more? Or less? Where does the carbon go? What does the future hold?”

Their efforts began to diagram the processes of a living, breathing Earth — the cycles of photosynthesis and respiration that balance the global atmosphere, and the human activities that can tip the scales.

Woodwell has worked cheek to jowl with many others at the leading edge of ecology and its real world implications. He’s worked with people who re-classified the kingdoms of life, discovered acid rain, and established the world’s longest running study of atmospheric CO₂, and with those who founded, in addition to the EDF, the Natural Resources Defense Council and the World Resources Institute. In this way, George Woodwell is a bridge between the origins of the modern American environmental movement and its future, from the now-textbook cases of nuclear radiation and DDT to the ongoing reckoning with climate change.

Woodwell and his colleagues tasked themselves with an accounting of anthropogenic change at a planetary scale. Half a century later, their work has left us with an alarmingly detailed balance sheet.

A New Center for Ecology

Eventually, George Woodwell said, “I did think that it was time to move on and do something different.” He talked about leaving Brookhaven with his wife, Katharine, “whose famous response was, ‘yes, George, you can go wherever you’d like to go. As long as it’s within fifty feet of salt water.’”

They found that proximity in Woods Hole, where Woodwell was recruited to start the Ecosystems Center at the Marine Biological Laboratory, which opened its doors in 1975. Houghton followed him there, and with other staff members they sharpened their focus on carbon dioxide and global change.

In global carbon equations, the work of solving for difference continued. Houghton said, “We’ve just been lucky in a sense, because both oceans and land have so far responded by taking up a little more than half of the emissions every year. There’s no reason why that should go on forever.”

In the mid-1980s, Woodwell again moved on, this time to start the Woods Hole Research Center, the institution to which he would devote the rest of his career (it was renamed in his honor in 2020).

Woodwell’s daughter, Jane, said “He had a year’s sabbatical from the MBL and we set up his office in the basement just to raise money that first year.” Home for the summer, Jane helped to write letters.

“When a foundation said no, we wrote them back and told them, ‘you’re wrong, you need to say yes,’” Jane said. “And they would say yes.”

“That’s almost literally true,” George said, laughing. “You can’t take no from a foundation.”

When Jane returned to college, her mother, Katharine, “came down into the basement and did my job. And way more. I mean, she and Dad did the Center together from there.”

Soon enough, Houghton left the MBL to join the Center. Others bolstered the ranks, like I. Foster Brown, an environmental geochemist who specializes in the Amazon basin and now coordinates the Center’s presence in Brazil.

They grew from a basement, to a church building, to a network of several more buildings until finally consolidating into a carbon-neutral campus in 2003.

The new building’s net zero design was ahead of its time, although not as far ahead as its founder, who installed a homemade bank of solar panels at his house in the 1970s. The center is built with recycled materials and designed for maximum efficiency with thick insulation, triple-glazed windows, and lots of natural light.

For the energy it does use, a bank of solar panels and a wind turbine sit steps away from the front porch.

“The goal was to be, if not off the grid, then carbon neutral over the course of a year,” said Houghton. “So in the summer months, we’d make a lot. And in the winter months, we’d use some of that. That would have worked, except that we had our own computers running, and they consume.”

The computers weren’t just running office programs — they were crunching through high resolution satellite imagery. “So we were using more energy to cool our computers than we were to heat our place in Massachusetts,” Houghton said.

Science in the Arena

Susan Natali, an Arctic ecologist who’s worked at Woodwell since 2012, is a project lead for “Permafrost Pathways,” an ambitious new effort to study the warming Arctic, factor its melting permafrost into climate models, and work with Indigenous communities to adapt to and mitigate the changes that threaten their ways of life.

She’s a typical scientist in some ways. “When I go for a walk, I’m usually thinking about carbon,” she told me.

In other ways, though, she is an embodiment of the mission-oriented zeal that characterizes Woodwell. She said, “When I got out of college I was like: Do I want to do science? Or do I want to do something that can have an impact? One of the things I really love about Woodwell, and why I stayed, is because I can do both of these things.”

The Center and its founder have never been afraid to wade into the fray. On DDT, nuclear war, and then climate change — catastrophic human interventions in the finely-tuned workings of the biosphere — George Woodwell took what he knew straight to the people he thought should hear it.

Houghton told me, “We landed in Woods Hole talking about climate change. I remember standing in a meeting in Washington, DC, somewhere in those days and saying, ‘climate is going to be a big one.’ And the response from the agencies was, ‘Well, come on. We’re worried about acid rain, don’t just give us a new problem.’ That was really it. ‘We’re full. We’ve got problems. Don’t give us a new one.’”

In the 1970s, as the country reeled from oil shocks, the Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations scrambled to find oil alternatives and to conserve energy. At the same time, a growing concern about fossil fuel emissions drew Woodwell into an effort among scientists, government officials, environmentalists, and oil companies to reckon with greenhouse gasses and recommend solutions for dealing with them.

In 1979, at the request of James Gustave Speth at the President’s Council on Environmental Quality, Woodwell authored a report with leading climate scientists Charles Keeling, Roger Revelle, and Gordon Macdonald, called “The Carbon Dioxide Problem.” They described serious changes to come, and warned that “enlightened policies in the management of fossil fuels and forests can delay or avoid these changes, but the time for implementing the policies is fast passing.”

Alarmed, government officials asked for a follow up from the National Academy of Sciences. This ad-hoc investigation became the Charney report, which is now seen as a major milestone in climate science. It largely confirmed the earlier research, and predicted global warming of between 1.5 and 4.5 degrees celsius if CO₂ doubled — remarkably consistent with modern scenarios. Its warning: “A wait-and-see policy may mean waiting until it is too late.”

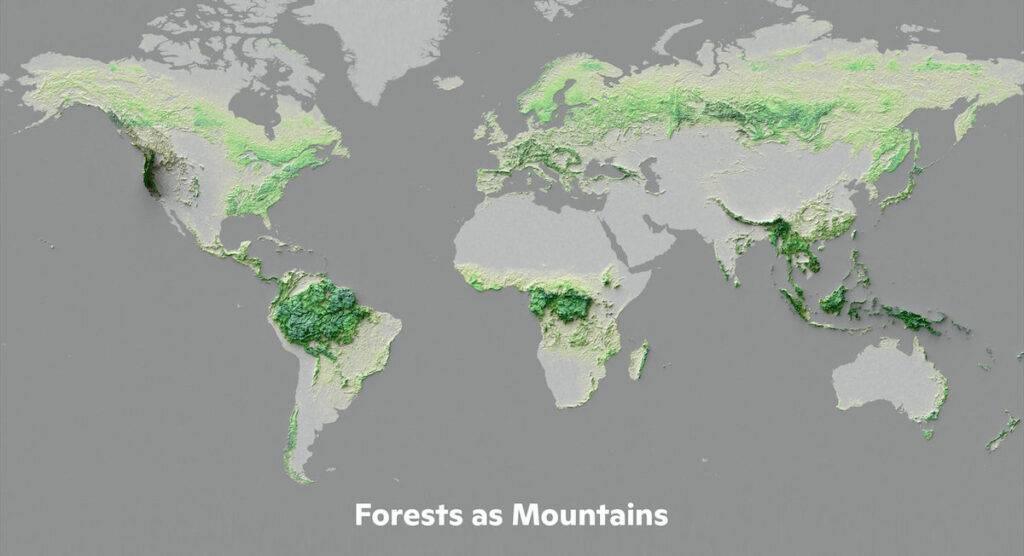

Credit: Data from Baccini et. al (2018). Map by Greg Fiske, Woodwell Climate Research Center

In the 1980s, Woodwell continued to work with policymakers on climate change, testifying before congress several times and contributing to influential reports.

Speaking before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources in 1980, Woodwell acknowledged that scientists might disagree on the details of global warming, but that “such disagreements are an intrinsic part of the search for knowledge and their existence cannot be taken as a reason for ignoring, neglecting, or failing to act on the central issues.”

“The series of problems associated with the carbon dioxide problem will become major issues in the next century whether we address them at the moment or not,” Woodwell told the committee.

Massachusetts Senator Paul Tsongas, the committee’s chair, jokingly retorted, “but the primaries will be over by then.”

“This set of primaries may be,” Woodwell replied. Later in his testimony, he expressed his confidence that “these are problems that well-governed, wise nations are capable of addressing successfully.”

“When you find one, let me know,” Tsongas said.

In congressional hearings, where Woodwell often testified alongside other well-known climate scientists like NASA’s James Hansen, his role was often to fill in the details of terrestrial ecology — the interactions of the living Earth with the chemical, atmospheric, and oceanic circumstances described by others.

He called attention to the delicate balance between photosynthesis and respiration, and the limits of scientific knowledge about how climate change will affect these processes. He warned that we were flying blind when it came to landscape change, that “it is madness not to have data flowing in regularly, monitored on a year-by-year basis, telling us what is happening to forests around the world.”

Woodwell, like many prolific scientists, was sometimes crunched for time. At one hearing, Rhode Island Senator John Chafee sensed a rush and asked, “Dr. Woodwell, what is your problem?”

“An airplane at 12 o’clock,” Woodwell replied.

“You have got more than a problem,” Chafee said. “You have got a disaster.”

But the committee bumped Woodwell’s testimony forward, and he proceeded to lay out the risk of carbon feedback loops, of methane being released from soils, of species not migrating fast enough to keep up with climate — plus the urgent need to get off fossil fuels, halt deforestation, and set up a monitoring system for understanding land cover change by satellite.

“Dr. Woodwell,” Chafee said, “if we are going to get a couple questions in and you are going to catch that plane, why don’t you wind it up fairly soon?”

He wound it up, but not before saying, “I think we know enough about this topic, and we have known enough about it for at least a decade to move toward alleviating the problem.”

In the early days, even companies like Exxon were funding climate research, including at Woodwell’s Center. By the late 1980s, efforts to alleviate other atmospheric pollutants were paying off, and it seemed like the greenhouse gas issue would be resolved the same way.

But Woodwell was right in the thick of things as what began as a team effort splintered into a contentious fracas. Small splinters, like when Reagan took the solar panels off the White House and appointed a dentist to head the Department of Energy, and large ones, like when the department axed funding for CO₂ research, and when, starting in the late 1980s, a coordinated campaign of climate denial forestalled significant action for decades to come.

In 1983, Woodwell wrote a portion of the National Academy of Sciences’ Changing Climate report, whose lackluster reception Nathaniel Rich, in his book Losing Earth, cites as a turn for the worse. Although the report said things like “we may get into trouble in ways that we have barely imagined,” its findings were downplayed by the Reagan administration and largely misinterpreted by the press.

Speth, reflecting on Woodwell’s 1979 carbon dioxide report, wrote, “In the 1970s and early 1980s, environmental issues were fresh, we environmentalists were constantly sought out by reporters. But the novelty faded, and so did editors’ interest.”

By the time Woodwell found himself on William F. Buckley’s TV show, “Firing Line,” in 1997, he had been invited there to argue against the premise that “the environmentalists have gone too far too fast,” and had to contend with the misstatements of fact and endlessly recycled “gotcha” questions that have come to characterize climate denial.

“Do you give up your airplane ticket tonight, and walk home?” asked Utah Senator Larry Craig.

“We have to live in the context of our time, we all have to do that,” Woodwell replied. “But that doesn’t mean we can’t change the context. We have to change the context.”

Science is how we understand real world problems. And not in a way that’s detached from daily life, he really sees it as being integral. This is about people. It’s about poverty, it’s about justice, just as much as it’s about trees, and forests, and ecosystems. And so in that regard, it needs to be really integrated into societal decision making, not something that’s separate.

—Heather Goldstone

Moving Forward

International climate negotiations have been proceeding at a somewhat steadier rate than domestic ones, and the Woodwell Center has been involved in those since the beginning.

In the 1970s, George Woodwell wrote reports for the United Nations Environment Program, and in 1987 helped organize key workshops in Austria and Italy, where scientists translated their consensus on climate change into temperature and emissions targets in the format that we often see today.

And he was by no means alone. Kilaparti Ramakrishna, who joined the Center in 1987, helped to draft the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, and has been deeply involved in international negotiations ever since.

Houghton, who has been a lead or contributing author on several IPCC reports, said: “You can see the evolution of what we can say with certainty getting stronger.”

Heather Goldstone, Woodwell’s chief communications officer and former host of WGBH’s Living Lab Radio, told me that attention on the Center’s research has picked back up in a big way, to the appreciation of those who work there. Although, she admits, the interest “would have been nice ten years ago.”

Although Woodwell and Houghton are both retired, the Center continues its tradition of science and advocacy. Its staff is involved in the nitty-gritty research and in scientific meetings at the highest levels, as authors of IPCC reports, and leaders of long running international research projects. Its leadership continues to hammer away at influencing policy, and increasingly, business.

Natali, the Arctic ecologist, said, “When you say ‘we want to get this into policy,’ unless you’re actually talking with policymakers, it’s not going to happen.’”

At times, she’s found herself in the same boat as Woodwell and Houghton did decades earlier, this time on the subject of permafrost. On a trip to D.C. just a few years ago, “I remember talking to Arctic policy experts, and that they weren’t thinking about permafrost, I really was kind of surprised,” she said.

Like with many things, George Woodwell had been ringing the bell on permafrost for a while. “George is an inspiration,” said Natali. “He was one of the early people talking about this.”

Goldstone summarized George Woodwell’s approach this way: “Science is how we understand real world problems. And not in a way that’s detached from daily life, he really sees it as being integral. This is about people. It’s about poverty, it’s about justice, just as much as it’s about trees, and forests, and ecosystems. And so in that regard, it needs to be really integrated into societal decision making, not something that’s separate.”

Reflecting on the progress or lack thereof during his lifetime, Woodwell says, “It’s been consistently not enough. Settling on how much we can allow the Earth to warm is a total loser, because warming the Earth in any degree dumps more carbon into the atmosphere. You’ve got to turn it around and cool the Earth now.”

Woodwell’s proposal has been for decades a vast reforestation and restoration of natural ecosystems, what have now come to be known as natural climate solutions. “The biggest, most effective way of getting carbon out of the atmosphere is photosynthesis,” he maintains. “It comes free. It works. And it works in all sorts of circumstances.”

Houghton told me, “the ecologist in me just says, ‘which has the longer track record? Are we going to let nature work for us, or are we going to replace nature?’ I think there are some people who think we should be able to do better than nature, and maybe we can do better than nature, but I just think you have to be careful.”

The Center has expanded its quest to understand the carbon budget and recommend climate solutions via Earth’s forests, soils, and wetlands. It continues the uphill climb of translating climate risk into policy action, and much of its recent focus has been on making science concrete and available for communities on the front lines of climate change.

From their modest base in Woods Hole, researchers at Woodwell show us, with increasingly fine resolution, what’s happening to the planet. Their suggestions are firm. The question left up to the rest of us is: Will that be enough?

What You Can Do

Check out the visuals on the Woodwell site; check out this cool StoryMap about the Woodwell Center’s work in Brazil.