A collage of creative, sustainable living.

It is a chilly June morning when I visit Ben Robinson and Betsy Carnie at the Barnhouse on South Road. I find them in the main house’s cold kitchen, bundled up in sweaters. Betsy hands me a beach rock, which has been warmed by the stove’s pilot light, and a cup of tea. Coat on, I wrap my hands around the rock, surprised by the comfort of its warmth, and join them at the kitchen table. None of the 43-acre property’s 11 structures have heat. Only a few have hot water and toilets. And much of the property has been allowed to rewild.

The Barnhouse, which was founded in 1919, is owned and run by a co-operative of 35 members, mostly relatives of the founders. Each member has use of the property for two weeks a summer, and part of the charter is that each member must participate in the maintenance and upkeep of the property, which has a beautiful rustic main barn where members eat their meals and congregate, a small main house with a commercial stove, and small bunkhouses dotted around the property. “This place was sought out as an alternative to the luxury of summer resorts like Newport and the Catskills.” Ben says. “The members are still trying to keep it simple. A few summers ago, there was a big discussion about whether to install the internet.”

Until I talked to Ben and Betsy and came across an article in the New Yorker a week or so later, I had not realized that communal living is on the rise around the country. Nathan Heller’s New Yorker article featuring the Treehouse Hollywood tells the story of an intentional communal living space in Los Angeles. The Treehouse Hollywood offers private rooms, bathrooms, sometimes kitchens linked by community spaces such as laundry, a library, and larger kitchen. In her popular 2020 book “Brave New Home,” Diana Lind writes about the value of shared spaces: “Co-living has grown popular because it meets several needs that single-family homes don’t: socialization, less consumer friction in everything from utility accounts to furniture, and the convenience of all-inclusive fees and shorter leases.” Because they meet so many critical criteria such as economy of space and resources, places like Atlanta and New York City are also exploring ways to adopt co-housing initiatives.

I ask Ben and Betsy if they were intentionally seeking this kind of living. Ben laughs. “No, we had two small children and were just trying to map out a housing plan. Eleven years ago, we found a small ad in the paper looking for a cook for the property. It seemed like it might solve our summer housing problem. We called the ad’s number, and have lived here for about six months a year ever since.” Betsy, who is the head chef for the Charter School, is in charge of the meals at the Barnhouse: breakfast, snack, lunch and dessert, dinner and dessert. Ben, who is a planner and designer, helps to oversee the maintenance of the buildings. Ben tends the property’s large garden. “The garden helps me stretch the Barhouse food budget. And the food tastes so much better,” Betsy says. In the winter, the family rents a home near the Vineyard Haven library. “We love it. The boys can walk to town, to the library, and I can walk to work,” Ben says.

For Ben, Betsy and their children Runar Finn and Odin, mitigating climate change is a bond and a way of life. The boys were key members of Plastic Free MV’s plastic bottle ban, and participate in the Sunrise Movement, a youth movement dedicated to stopping climate change and building a green economy. Ben sits on the Martha’s Vineyard Commission (MVC), is chair of the MVC’s climate task force, and sits on the Tisbury planning board. Betsy has transformed the Charter School’s food offerings — making moves to make it as low-waste as possible, and taking advantage of the incredible local food available. Charter School students are served snacks on foraged grape leaves, and lasagna with Slough Farm or Grey Barn meat. Betsy uses her clear glass lids — found at the Dumptique — that she places over bowls instead of foil or plastic wrap as an example of how to cut down on kitchen waste. This has two advantages. “First, you can stack the bowls, and second, you can see the food, which makes it much more likely to be eaten,” Betsy says. The family tries not to fly, and they use the Island’s VTA as much as possible. “We taught the kids how to use the VTA early. It gives everyone freedom,” Ben says.

Though I have known Ben since childhood, I didn’t know Ben and Betsy’s story. Betsy grew up in Milton, but came to the Island in the summers: “My dad was a schoolteacher. His family had a place on East Chop. I got my cooking skills from my mom.” Ben grew up on the Island, spending two years in Asia from age 5 to 7. “I am one of five kids,” he says. “My mom is from Finland. She cooked on a wood stove. Wasted nothing. She was one of the founders of the original food co-ops on the Island, an early proponent for a bus system on the island, and founded the crosswalk program for the Tisbury School. I have never been a consumer by nature. But I guess some of this nonconsumption is from her.” Ben’s father is a builder on the Island, and a passionate sailor, which Ben inherited: “I love the fact that when you are offshore sailing, you have to have everything you need with you. It is often very little. You are ultimately responsible for yourself. You have to look ahead, plan, adjust for the weather. This kind of thinking lends itself to architecture, where you have to anticipate everything. And you are always learning to live with nature.” He laughs. “I love the pace. The time on a passage and the structure of the days,” he says.

Betsy went to Wellesley, and then got her master’s from Columbia’s Teachers College. They were introduced by a mutual friend, the jeweler Gogo Ferguson. “I remember seeing him walk into Gogo’s shop [Gogo Ferguson used to have her jewelry shop across from the Black Dog on the harbor] and thinking, ‘That’s my man.’ I was cooking and traveling a lot then. So was he. We didn’t have cell phones, so we wrote each other letters. At some point he came to visit me when I was teaching on Cumberland Island in Georgia. He had a lunchbox as his travel bag. Just a shirt and a toothbrush. I loved that he traveled that lightly,” she remembers.

So here they are 20 years later, continuing to live these values. Of course they know that one family is not going to solve the climate crisis, but they do not want to contribute to it. Ben — who has an encyclopedic brain for climate statistics — notes that if the entire 7 billion people on the planet consumed as much as Americans do, we’d need five Earths to support it.

“Nobody wants to give up their lifestyle. No one wants limits. It’s a problem,” Ben says. Betsy adds, “Everyone wants shiny and new. Why? It’s not like our family suffers living the way we do. I have an enormous amount of pleasure and joy in my life. We eat exceptionally well. And look at where we live,” she says, pointing to the verdant grass and trees outside the kitchen’s window. “I loved the movie The True Cost. I think about that phrase a lot, and ask myself, ‘Who is my purchase affecting? What impact will it have on the environment and communities far from here?’”

“In the old days, people came here to live a different life. Somehow we lost that,” Ben says.

Betsy agrees: “Everyone used to have ‘Island cars.’” These were beat-up jalopies dedicated to transporting folks from the boat to their homes, the market, and the beach. “Even the summer residents lived with a sense of thrift and community,” Ben adds.

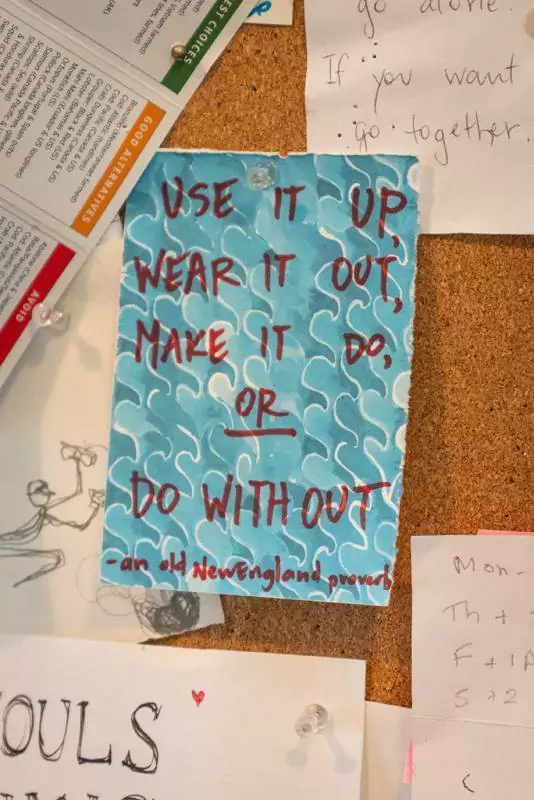

Betsy points to the wall, “I put that saying up.” A sign reads, “Use it up, wear it out, make do, or do without.” “Doing without is an option,” she says. “It is an adventure. And I believe there is more genuine happiness in living this way.”

When Betsy first started cooking at the Charter School, the school offered bananas, oranges, apples, and dried fruit as a snack. Betsy wondered why they were offering oranges in September. She scrapped the snack plan, sourced local pears and apples, and served them with a sign that identified them as “Island” fruit. Betsy says, “They were not as pretty as the store-bought ones, but they were delicious — crunchy, juicy. As soon as the kids tried them, they were hooked. There was also great pleasure in knowing that these were pears and apples from their island. In January, when it was orange season, I served citrus. And then in the spring, we had watermelon and berries. Everyone tasted the specialness of it.”

Beyond their summer communal digs, Betsy and Ben also espouse the idea of a sharing economy. Betsy uses the example of sharing a popcorn machine with Native Earth Teaching Farm. “She needs and uses the machine in the summer. I need and use one in the winter. So both of us don’t need our own machines. Before I was the chef at the Charter School, they served Smartfood as a snack. Now the children get freshly popped, organic popcorn — much less waste, much better for the kids and planet.”

And Ben shares the story of their search for surfboards: “We asked around. Of course there were people here with extra or old boards.”

Betsy nods: “Yes, it’s that kind of thinking that makes a difference. Sometimes it feels weird or uncomfortable to be asking — it’s always easier to be the person who is giving — but this is how community and relationships are forged. I have relationships with people I would never have had if we didn’t live this way.”

“We have given up a certain kind of security,” Ben concedes. “And we are fine with that, because we are willing to figure it out.”

“Everyone wants shiny and new. Why? It’s not like our family suffers living the way we do. I have an enormous amount of pleasure and joy in my life. Look at where we live.”

Ben shares that he feels conflicted about designing houses. “But I guess I rationalize it in some way by recognizing that I’m helping people think about what they need. How they want to live. That’s an important conversation.” Because we are already living far outside the sustainable boundaries of our finite planet, we must “greatly reduce our output of both material and energy.” This means “deeply considering the investment and impact of any project.” He sighs, “Really, the best thing to do is not to build new, but restore and improve energy efficiency of existing structures. And consider the material and energy impact of the project, think small, quality over quantity. Also consider the materials you use, for the health of the user, the health of where they are sourced, and the health of where they will ultimately be disposed.” I love that he points out that human labor is a renewable resource — the livelihood for many families. So regular maintenance provides a reinvestment in the already built and our community. He also stresses that people really need to “consider what is truly sufficient to meet your needs, regardless of your desires, wealth, and status.”

Betsy laughs, “Ben also spends a lot of time thinking about shoes.”

“It’s true,” Ben nods. “It’s true. They are such a necessity of life. You can’t live without them. There are not a lot of sustainable options.”

I appreciate Ben’s point. Yes, there are certain things that are, like shoes, necessities. But even with necessities, let’s think about what we buy, how many we buy and will sincerely need.

Spending time with Ben, Betsy, and their children challenged me to think about my life and home. A greener lifestyle is not about deprivation, it’s about discernment. Needs versus wants. Borrow versus buy. Yes to less, and that this somehow feels blessed.

Advice from Runar Finn and Odin Robinson on how to live more sustainably:

“Buy No New Stuff. Challenge yourself to buy nothing new for one year. If you need something, try to buy it used locally (Thrift Store, Dumptique —reopening any day now — MVStuff for sale).

Or try to borrow/share it. Or consider an alternative. Or go without it. If you’re able to go further to support NoNewStuff, volunteer at the Dumptique or thrift store.” –Odin

“Involve yourself in politics whenever you can — from the local to national level. Individual choices only go so far in regulating our consumption and transforming our society. If we really want to change things, we need to focus on collective decisions.” –Runar Finn

I love this. I see cooperative communities as the way of the future Thank you for making the right kind of footprint! I just love what you are doing and I hope your vision inspires others to do the same. Building a new grid and living model at the grass roots level is how we will transform the planet. Thank you!!

Great story about the life and times of Ben and Betsy. Thanks for sharing, Mollie.

My new book, Martha’s Vineyard in the Roaring Twenties, explores the origins of Barn House and the people who gathered here in the 1920s, from Roger Baldwin to Felix Frankfurter to Norman Thomas. Their Chilmark neighbors feared Barn House members were radicals about to take over the country! Actually, they savored the communal living, the conversation and conviviality offered at Barn House. That was 1919, and it sounds as if it is still alive and well a century later.

Three cheers for Barn House, then and now.