Not only can regular people do real science, the process could prove healing for individuals, communities, and the Earth.

For the past 15 years, mental health practitioners have been on the lookout for a burgeoning complaint: eco-anxiety. The condition refers to a chronic sense of environmental doom, a fear that the ecological systems that sustain life are on the brink of collapse. Most psychotherapists interpret eco-anxiety not as a pathology, but rather a normal response to real-world conditions.

How do they recommend we mitigate that fear? Two measures: action and community. Sure, we can reduce our plastic waste, buy local and organic, but there’s a lingering feeling that these individual choices are never enough. We need a more powerful antidote. While it’s obvious there’s no panacea, we all possess one superpower that could aid in the fight: the power of scientific observation.

Hold up, you might say, I’m no scientist. I’m a [bartender, bookkeeper, insert other rationalization here]. But science is for everyone, no degree required. And one particular form of science, citizen science, is specifically concerned with returning the power to the people.

Citizen science happens when public volunteers participate in the scientific process to address real-world questions and concerns. Anyone can join in, usually by following a uniform protocol to collect data. Then scientists analyze and draw conclusions from that data. But it’s more than free crowdsourcing for scientists. Citizens benefit from the educational opportunity, as well as from the return of the data, which can influence policymaking and other decisions that directly impact their local environments.

Citizen Science, Abundant On-Island

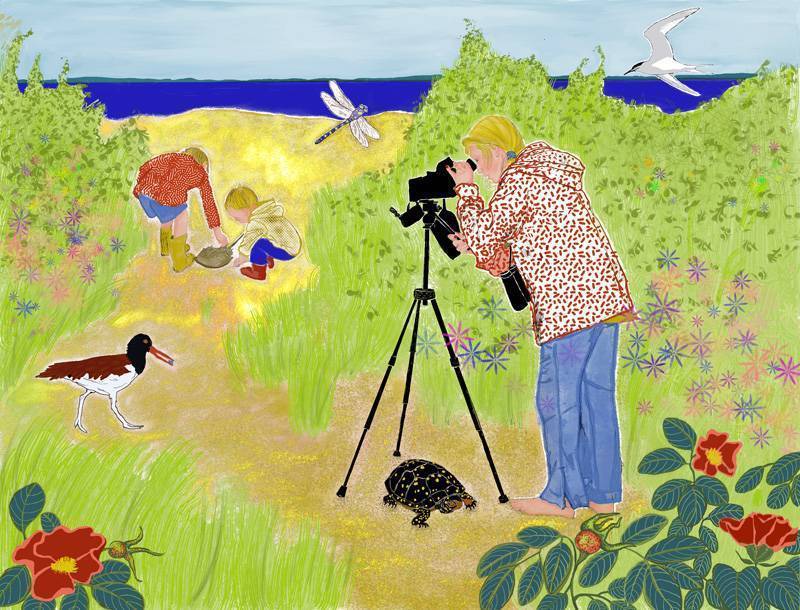

Here on Martha’s Vineyard, there are many opportunities to get involved in citizen science, with organizations like Felix Neck and BiodiversityWorks leading the charge. Owing to the Island’s prevalence of rare species and conservation land, most of the current projects involve monitoring local wildlife populations. Other ventures, from the Martha’s Vineyard Commission and the Buzzards Bay Coalition, call on citizen scientists to help assess the Island’s water quality, using test kits to screen nitrogen and cyanobacteria levels.

Perhaps the most visible programs are the beach-nesting bird initiatives, which are responsible for many of the summer rules on our beloved stretches of sand. The exclosures, the fencing, the leashed-dog mandates — these all exist to protect vulnerable piping plovers, oystercatchers, and terns.

“They’re nesting on our beaches during the summertime, when everyone else wants to be using the beaches as well, so it’s real all-hands-on-deck work,” said Liz Olson, assistant director of BiodiversityWorks. The program relies on volunteers to help with data collection and habitat protection. “To have a well-functioning program doing the best we can do, we need help, and volunteers are a great way to get that help,” Olson said.

There are a number of other survey projects happening across the Island, tracking species like spotted turtles, horseshoe crabs, ospreys, odonates (dragonflies and damselflies), spadefoot toads, and salamanders. But interested volunteers aren’t limited to these creatures. A new project from BiodiversityWorks, called the Martha’s Vineyard Atlas of Life, encourages citizen scientists to record pictures and observations of any flora and fauna, using the inaturalist app.

As Atlas of Life director Matt Pelikan states, the project is about establishing a baseline for species on the Island. “Compiling the knowledge of what’s here, how common it is, and where it occurs seems like a very basic first step in protecting it all more effectively,” Pelikan said. That knowledge could come in handy when it comes to understanding and combating climate change on-Island. “The sooner you can start gathering data, the better you’re going to be at detecting changes later on,” Pelikan said. “Citizen science is a really powerful way to get the breadth of coverage, and the real, sustained, ongoing coverage that you need in order to track that sort of thing.”

The Snowball Effect of Data

One of the Vineyard’s most successful citizen science projects, the osprey survey, is part of a global strategy to monitor indicator species of our planet’s overall aquatic health. In the early 1970s, nesting ospreys on the Island had dwindled to just two pairs. Volunteer efforts to construct nesting poles and monitor birds have been wildly successful. Last year, Felix Neck reported a record-breaking 106 nests.

But the impact of citizen science is not strictly local. Some data collected by citizen scientists make its way off-Island, where it contributes to state, and even federal, conservation decisions.

The data that shorebird volunteers collect — number of nests, number of hatchlings, survival rates — is sent to MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage Endangered Species Program. This helps determine the productivity of birds like plovers at a state level, and tells managers which practices are working to protect the species.

All data collected at Felix Neck is incorporated into Mass Audubon’s Statewide Inventory and Monitoring Project, to provide a statewide view of biodiversity and change over time. The data can, and has, impacted the commonwealth’s management of species.

Director of Felix Neck Suzan Bellincampi said horseshoe crab surveys were instrumental in changing harvest regulations that were leading to a decline in populations. “When we first started doing the surveys, horseshoe crabs were being harvested during their reproductive cycle,” Bellincampi said. The commonwealth changed the harvesting season to protect reproduction, and numbers recovered. “That’s a concrete example of the work these citizen scientists did to actually make a difference in statewide regulation,” Bellincampi said.

Other citizen science projects reach even farther. The amalgamation of data from water quality testing, which follows guidelines from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, has allowed researchers to study decades of change in Buzzards Bay. The data may come from local waters, but it sheds light on issues like temperature rise and human development that impact coastal waters worldwide.

Initiatives like the annual Christmas Bird Count and the North American Breeding Bird Survey supply the data behind the United States Geological Survey’s official estimates on bird populations, density, and distribution. These numbers inform the conservation priorities of federal authorities, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Park Service.

“Over time, those databases become really, really powerful,” Pelikan said. “You can track the change in distribution of species in response to climate change. You can compare that to models to see if the models are accurate, then refine the models so we’re better able to project what might happen in the future.” In other words, participants may count only a few birds, but the data can reach around the world.

The fact these biologists have a use for me and an appreciation for what I do is rewarding. It’s the most satisfying thing I do in my life. —Keren Tonneson

The Community Connection

While collecting data and watching it grow might address the “action” element of eco-anxiety, the “community” facet is just as important. Felix Neck prefers to call its citizen science programs “community science,” in order to emphasize the inclusive, homegrown nature of the projects. Other organizations evoke the same sentiment.

“It’s important to have the community involved in this process because these resources all belong to the community,” Olson said of the BiodiversityWorks projects.

“Conservation is partly biological, but it’s also a social problem,” Pelikan said. “It’s based on people’s attitudes.”

Citizen scientists involved in the projects say that apart from viewing and learning a great deal about local wildlife, some of the most rewarding work involves educating the public about what’s at stake.

Keren Tonneson, a volunteer with BiodiversityWorks for 10 years, keeps her summers free to spend time with the plovers. When she noticed fishermen at Lighthouse Beach leaving scraps that could potentially attract predators, she politely conveyed her concerns. In turn, the fishermen began educating other beachgoers about the importance of leashing dogs, respecting fenced areas, and using caution while flying drones. “The fishermen that are out there all the time are aware of their surroundings, they have a connection,” Tonneson said. “I’ve made them my allies.”

Ulrike Wartner, another BiodiversityWorks volunteer, said it’s satisfying to pass this information on to young people. “It’s kind of fun, and it usually goes really well, if I can talk to a kid about the birds,” she said. “I can show kids the birds, and even rope them into starting to feel protective.”

Wartner says these efforts do feel like small steps toward addressing climate change. Perhaps not in a systemic, big-picture way, but in “micro-ways, thinking about what you personally can do and also how you can educate the community.”

For Tonneson, learning about the birds and handling the data has sharpened her belief in herself as a scientist. “I realized a little late in life that I wished I had gone to school for this,” she said. “The fact these biologists have a use for me and an appreciation for what I do is rewarding. It’s the most satisfying thing I do in my life.”

Science Is for Everyone

That’s really the heart of citizen science — amateurs and laypeople believing that we can be part of the solution.

“You don’t have to have any experience, you just have to have passion,” Olson emphasized.

“Everybody starts somewhere,” Pelikan reiterated. “And anybody who is capable of making good observations can do science.”

The benefit of participating in citizen science through organizations like BiodiversityWorks and Felix Neck is that they provide a scaffolding of educational support from scientists.

“We are also educators at heart,” Bellincampi said. “We can translate the concepts into bite-size pieces. It makes science relatable and understandable and doable for everyone.”

Pelikan also points out that technological advances such as digital photography, smartphones, and apps like iNaturalist have made contributions to scientific data sets more accessible than ever.

The more involvement, the more data, the better. On-Island, simple contributions like collecting data in your own backyard can make a huge difference in achieving the widespread coverage these citizen science projects require. For that reason, the scientists involved say they don’t want any barriers to access.

“You don’t need special degrees, you don’t need fancy equipment,” Bellincampi said. “We really want everyone to be able to partake and spend time in nature.”

Whether you spend hours scouring the dunes for shorebirds or a few minutes checking the osprey pole on your bus ride to work, take comfort that your time outside can be more than a diversion. It’s more than reverence for an at-risk Earth, too. It’s getting to know the ins and outs of your environment, connecting with your community, and playing a small scientific role in a big scientific picture.

“This is a real thing, it’s not just a fad or a hobby,” Pelikan said. “The science part of citizen science is very, very real.” And it may be just the salve your eco-anxious nerves need.

How Do I Get Started?

If you’re ready to begin the citizen science experience, a number of projects are actively recruiting volunteers. Projects on-Island include:

BiodiversityWorks Volunteer Program

Martha’s Vineyard Atlas of Life

Buzzards Bay Coalition; Baywatchers

Martha’s Vineyard Commission; Water Quality Testing

Islanders can also join in countless off-Island citizen science projects. Activities range from playing an online game that catches Alzheimer’s symptoms in mice (with StallCatchers) to walking around with your head in the clouds (for the NASA GLOBE Observe project). In most cases, all you need is a computer or a smartphone. Hop on a website like scistarter.org or CitSci.gov to search for projects by location, age group, or topic of interest.