When Tom Chase was growing up in downtown Oak Bluffs he experienced a profusion of wildlife. Bobwhite quail were everywhere, “under everyone’s bird feeder,” and their namesake call was heard all over town. Enormous rhinoceros beetles flitted around the lights of hotel windows, and walks with his childhood friends were an odyssey of field and forest, often just a few streets away.

Not to mention the snakes. “All the kids coming home from school would go by Whiting Milk Company, and flip the sheets of tin down there and catch snakes,” Chase said. “And there used to be little elvers, baby eels, going up the creek and back at Sunset Lake. My life was filled with wildlife everywhere I went.”

“Then there were these places,” Chase said, “that were just so beyond belief, they were so exquisite.” He remembers Fresh Pond, a kettle pond near Sengekontacket, as “this wild, wild place that had one house on it.”

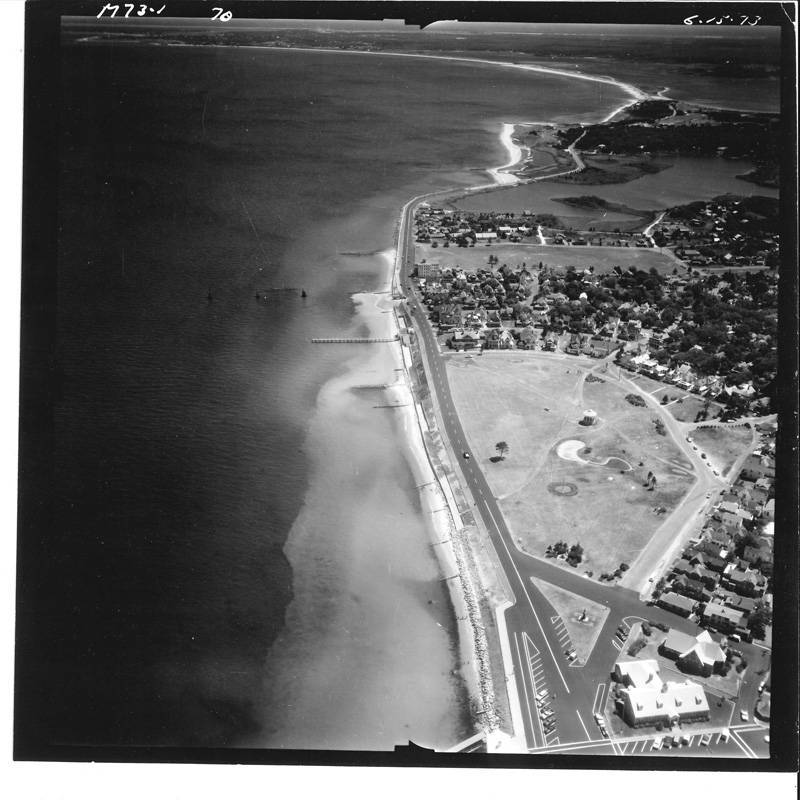

“And now it’s surrounded by development,” Chase said. The map has filled in, and in half a lifetime, places all over Oak Bluffs are now houses with yards. “And that’s the story that’s told by every conservationist everywhere on the planet,” he reflected. “Of how it used to be.”

But Chase, a longtime ecologist on Martha’s Vineyard, was only waxing nostalgic at my request. He doesn’t see the backyards of Oak Bluffs, Edgartown, or anywhere else as doomed. Instead, he and others on the Island see thousands of acres of potential wildlife habitat.

These acres just need a little work.

Chase’s vision: Convert one in 10 Vineyard backyards into hyperabundant habitat for native animals, sources of life so productive they overpower the mortal devastation of suburbia. By working together for wildlife, he thinks, neighbors can also nurture a local aesthetic that prizes native plants, sandy soils, and all the other idiosyncrasies that define Island biology.

“He has bats in his bat box,” said Luanne Johnson, director of BiodiversityWorks. That may not seem like a nice thing to say, but it’s a big compliment — especially for Chase’s small backyard. She added, “He’s had river otters show up.”

It’s true. Chase has turned his own yard into a haven for wildlife. His work shows it’s possible to create an oasis of abundance visited by wild birds, mammals, reptiles, insects, and neighbors, even in the heart of Oak Bluffs.

The Map has filled in, and in half a lifetime, places all over Oak Bluffs are now houses with yards. And that’s the story that’s told by every conservationist everywhere on the planet … Of how it used to be.

– Tom Chase

Now, Chase has a plan with BiodiversityWorks to supercharge habitat in yards around the Island. The nonprofit has plenty of experience working with local landowners. “I always say that we’re kind of like ‘wildlife without borders,’” Johnson said. “A lot of people don’t know what the best thing is to do for the wildlife on their property, and a lot of them are looking for input.”

Those people, and their neighbors, are an indispensable part of an Island-wide conservation strategy. “Roughly speaking,” Chase said, “a third of the Island is conserved, a third is developed, and a third is up for grabs.” The remaining third is much more difficult to set aside for conservation, and the areas already protected are not enough to sustain the Island’s native wildlife.

“There’s some great news, and there’s some misleading news,” Chase told me. The land the Vineyard has already conserved is an incredible achievement, but, “many species, and almost all ecological processes, require large, intact landscapes. Much of the landscape we’ve conserved is in parcels of land that are too small to hold a viable population of a given species.”

Johnson agrees. “What we increasingly find is that the conservation lands that we have set aside just aren’t enough for connectivity, for our animals to be able to maintain their population,” she said.

Angela Luckey and Luanne Johnson,

of Biodiversityworks, inspecting a screech owl box. —Photo by Jeremy Driesen

“A river otter, or northern long-eared bat, or spotted turtle, they don’t look at who owns the property,” she said. While the big parcels like the State Forest, Long Point, or the Land Bank’s many acres of down-Island woods are crucial, they are isolated. In between lies a checkerboard of residential development that forms a gauntlet for wildlife. If enough spaces on the board are improved and connected, Chase and Johnson say, that gauntlet could become an olive branch.

Lawn is our country’s largest irrigated crop, but it doesn’t nourish much of anything. It’s “a biological desert for most wildlife,” Johnson said. Often, the more money people spend on landscaping, the worse their lawns get for wildlife. One National Science Foundation study found that higher-income households all across the country had less biodiversity on their lawns, likely as a result of more money for weeding and fertilizers.

“People already spend enormous amounts of money and time managing their yard,” said Chase. “We’re just asking [them] to convert the money that they already spend into different things. Spend your money differently, spend your time differently.”

For Chase, this goal is equal parts biology and social movement. In order to improve habitat on an ecologically effective scale, “we need to get beyond the individual backyards to the collective backyards, whether those are neighborhoods, or multiple property owners associated through social networks, or communities of faith, or whatever it is,” he said.

The aesthetic of the American lawn is entrenched, well-studied, and part of a long history. Transforming it on a cultural level is a big project. This is where Chase’s vision, of building critical mass using connections between neighbors, offers a foothold. It doesn’t force a change on people who don’t want one — but it suggests a practical course of action for those who do.

Chase has turned his own yard into a haven for wildlife. his work shows it’s possible to create an oasis of abundance visited by wild birds, mammals, reptiles, insects, and neighbors, even in the heart of oak Bluffs.

During a pilot run of this idea by Chase and his colleague Matt Pelikan at the Nature Conservancy called the Vineyard Habitat Network, this approach seemed to pay off. Chase said, “What we found is, by the time we got to the kitchen table, they were already in! The question was, ‘What do you want me to do?’ That always led to a walk around the backyard.”

“And when you walk around someone’s yard,” Chase said, “you can say, ‘Look, that oak tree right there? Oak trees feed more organisms than any other group of plants in North America. Keep that oak tree.”

“People love to find out what they actually have,” he said. “They didn’t know what it was, or what they should do, but they got so thrilled at knowing that they actually owned something that had history, and had meaning, and had wildlife.”

This brings Chase down to brass tacks: What practical steps can one person take in the backyard? The basics are easy, according to Chase. First, work with what you’ve got. No need to tear everything up, he said, because “the native plants you have are usually there for a good reason.”

Second, water. “Everything needs it, and many species of wildlife orient towards it,” says Chase. His own homemade pond is a key resource for many species, even if a few of those species are known to eat his goldfish.

Third, cover. This is in the eye and the size of its beholder. Snakes, which on the Island are harmless to people and help keep prey populations in check, like simple boards or corrugated tin to hide under, while other species prefer dense shrubs of the kind rarely found in the suburbs.

Last, and with the most potential for eager gardeners, is to seek and encourage native plants. “Some native plants, like oaks, are the breadbasket for so many invertebrates and the vertebrates that feed on them, as birds do on caterpillars,” Chase said. “Other plants are good at absorbing toxins, or act as host plants for pollinators.”

Gus Ben David’s yard backs up to Felix Neck in Edgartown, and hosts a diverse population, including this alligator snapping turtle. —Photo by Jeremy Driesen

There are so many ways to approach each of these steps, and such variation based on the qualities of the land itself, that Chase recommends whichever measures you have the time and the resources to pursue. Small inroads are still helpful ones.

Matt Pelikan, another Island biologist who keeps a close eye on his back 40, has noticed a surge of native insect life since he began his own regimen. What’s the regimen? “To be honest, my wildlife landscaping involves a lot of doing nothing,” he told me. “I knew I wanted to support wildlife, and I knew I wanted to cut back on yardwork. So I stopped mowing, stopped tending the beds and borders, and just kind of let stuff happen.” The dividends were clear.

Of course, many national organizations offer similar advice — food, cover, water, native plants. But this can be daunting unless you are a botanist or wildlife biologist. “What most people want to know, says Chase, “is, ‘What is the wildlife that is relevant in my neighborhood? What can I do in my yard?’”

“If someone lives in the sandplains, they’re not going to be able to grow the kind of trees that grow out of the moraine, because it’s really crappy soil, and the wind is howling, and there’s salt spray everywhere,” said Chase. “So where you live does constrain some things that you can produce. Understanding where you live also tells you where you have the greatest opportunities: which species of butterflies, which species of snakes, which species of shrubs.”

That’s where the biologists come in — in particular, a botanist named Angela Luckey, who just got a MV Vision Fellowship to work with BiodiversityWorks to help Islanders improve their backyards. Mentored by Chase, she will help landowners identify what’s in their yard now, and what could be there with a little help from the neighborhood.

In Chase’s yard, several new plants showed up on their own, like Venus’ looking-glass, a delicate purple wildflower that rivals some ornamentals. Once the ecological processes in a yard start rolling, all sorts of latent potential gets unlocked, from dormant seeds hidden in the soil to curious creatures who soon encounter the fresh new digs.

In the end, it’s about shifting our relationship to land from one of style to one of substance. “Land is here to support life. Human and wildlife,” Chase emphasized. “The popular myth is that it’s mostly a cosmetic, maybe a recreational kind of amenity for the Vineyard. But if you want clean water, if you don’t want to smell chlorine when you turn on the tap, if you want your garden pollinated, if you don’t want so many deer, if you don’t like getting bitten by ticks, if you don’t want Lyme disease” — well, you better get to work.